When governments around the world began establishing coronavirus advisory panels in the midst of the first wave of COVID-19 cases in 2020, their memberships brimmed with the titles one might expect: virologists, epidemiologists, behavioral scientists and engineers. One notable exception, however, came in Germany, where the government augmented scientific advisory work by turning for advice to philosophers, historians and theologians. And as the situation developed over the spring and summer, many states and nations embedded in their recovery plans targeted relief funding for visual, literary and performance arts.

Amid the important scientific, medical and policy work that has been the focus of media attention, such an eye toward the arts and humanities is a reminder of their importance in times of crisis — for telling us who we are, where we have been and where we might go.

Our current pandemic has led so many of us to look back at previous major plagues — the Great Plague of Athens, the Antonine Plague in 165, Influenza in 1918–20 and HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, to name a few, says Michael Grillo, University of Maine associate professor of art history. But Grillo, a scholar of the late Medieval period, is particularly interested in the art that emerged in the wake of the Black Death of 1348.

The plague “forced societies to reexamine themselves, first reactively in immediate survival mode, but then in a more contemplative manner as people recognized the gravity of their times,” Michael Grillo

The plague “forced societies to reexamine themselves, first reactively in immediate survival mode, but then in a more contemplative manner as people recognized the gravity of their times,” he says.

Sarah Harlan-Haughey, associate professor of English, agrees.

“In that period, when we look at the cultural artifacts that remain to us, we see that epidemics disrupt routine, damage communities and end lives,” says Harlan-Haughey. “If there is a silver lining to be found, it is that those who survived reexamined their role in the world, looked hard at life and death, and approached the questions about why we are here differently.”

Harlan-Haughey notes that 14th-century England saw a boom in cultural production after the plague struck and receded: visual art, music and poetry.

“People who were still alive seemed to want to live life to its fullest, and perhaps to leave something meaningful behind,” she says. She points to Geoffrey Chaucer, in whose work we find virtually no explicit references to the plague. But “the sense of the tenuousness of human society, the frailty of the individual human life, pervades his writing and makes it the masterpiece of humanism it is.”

Grillo, in turn, points to the architecture of Florence in the wake of the Black Plague, as conspicuously vacant spaces — “splendid palaces, fine houses and noble dwellings,” in the words of the poet Boccaccio — became indexical markers, constant reminders of the dead who had once made up the fabric of the city, and ultimately paving the way for new models for art that emerged in the Renaissance.

For Grillo, the plague then and COVID-19 now are “cathartic moments, which rather than simply clearing away the old for an unprecedented new, instead force a moment of contemplative reflection.”

In light of the disruptions presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, we turned to the community of musicians, visual artists and writers at UMaine, and asked them to reflect on what the last several months have meant for them, their practice and their work.

Susan Smith

DIRECTOR OF THE INTERMEDIA MFA PROGRAM

My artistic practice is focused on examining the struggles of displacement and making the invisible visible, using research to make stories heard. As we entered into lockdown in March 2020, I had just returned from a trip into the Sonoran Desert, using GPS data to create memorials for migrants whose lives were lost seeking asylum in the United States. As my attention turned to teaching hands-on artistic processes through Zoom and video tutorials, and creating online programming for fall for the Master of Fine Arts students, the numbers of lives lost from the pandemic mounted.

As artists, I feel it is our responsibility to situate our work right in the middle of what is happening around us, to lean into the discomfort that is there, and not to turn away.

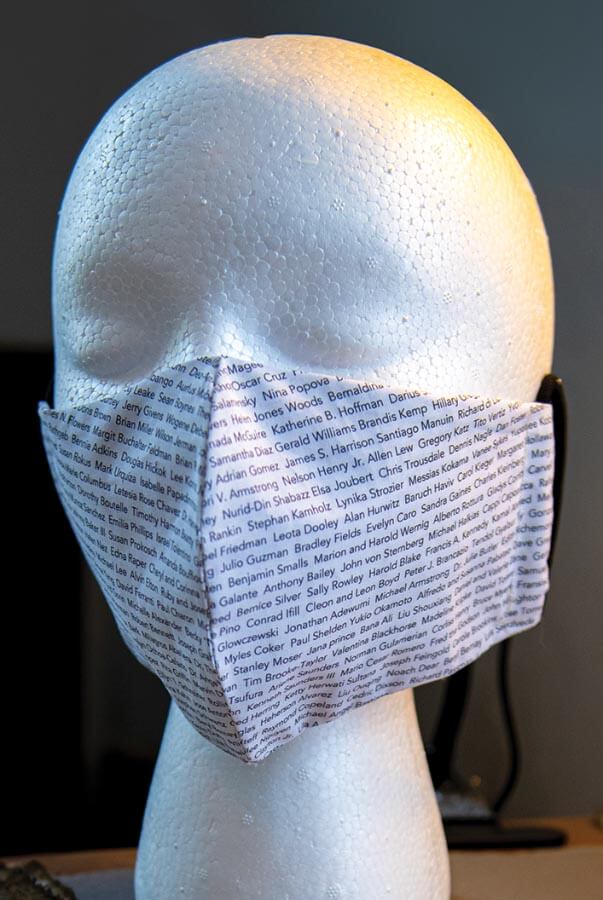

screenprint on cotton

The pandemic has hit hardest those least able to defend themselves against it. While I was able to transition to teach from home, millions of others were forced by necessity to go to work every day or were among the millions who lost their livelihoods and, for many, their lives. As the inequities that are part of everyday life across the country came into focus, the pandemic came ever closer into my own life, touching my family, and that sense of loss became the impetus for a series of work: “Mourning in America.”

As we inched closer and then exceeded the number of lives lost in U.S. service during WWII, speaking the names and reading the families’ accounts of their loved ones seemed the way to give the respect and attention these individuals deserved. Listening to the data and statistics in many ways allows us to remain detached from folks such as Zach Leviton, 16, of Chicago, Illinois who died of COVID in April, and whose mother talks about his love of movies and video gaming. I read the memories of the family of Taraben Amin, from Rockaway, New Jersey who died of COVID on Oct. 29. “A super mom who never complained nor made excuses and always found something to laugh about,” wrote her daughter.

I have spent many, many hours reading hundreds of such narratives, and this act of witnessing is as much a part of the art practice as is the creation of yards of cloth imprinted with the roster of names and translated into fabric masks. I feel a responsibility as an artist and as an educator to humanize the statistics we hear. It is easy to become numb to the trauma if we do not find a way to humanize the toll that it’s taking on our neighbors, our friends and our loved ones.

Jennifer Moxley

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

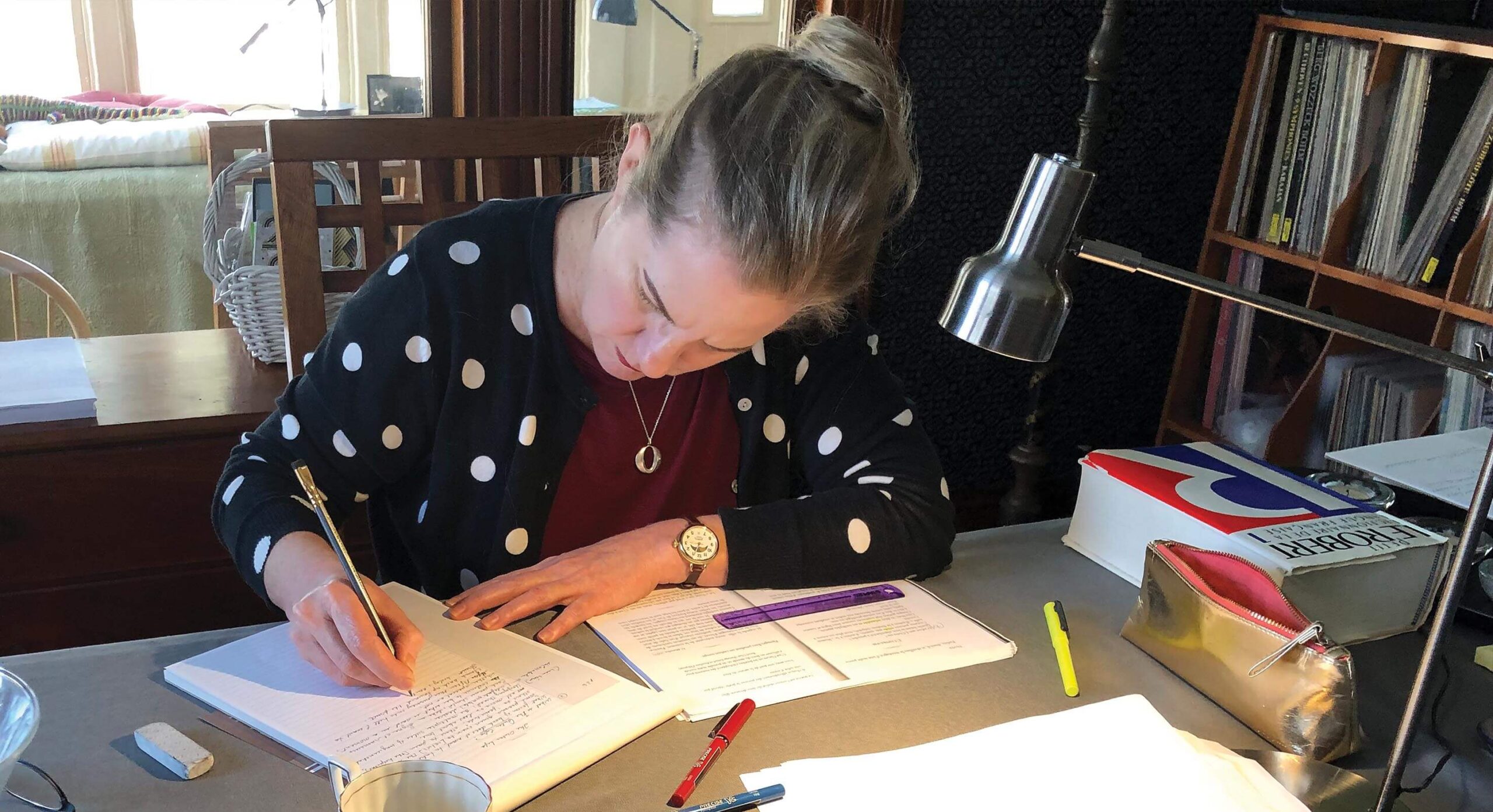

Important sociopolitical events boss artists around. They say: this is what you must think about, this is what you must address. I stubbornly resist such voices, even when I can’t shut them out. After 9/11, it seemed to me that some poets were penning their poems to the towers before the second one fell. I resisted. I needed time to process. I felt similarly during the first few months of the COVID lockdown. I didn’t write. Of course, I was also finishing the semester, supporting students and working on coping strategies. And I was glued to the news, like everyone. “I don’t feel like writing about politics or pandemics,” I thought. So instead, I read War and Peace.

Tolstoy’s genius at vivifying the complexities of the interior life against the large-scale canvas of the Napoleonic wars was an antidote to my creative lethargy. At the novel’s end my muse hesitantly crept back. I wrote a poem titled “Inside the Shell,” which obliquely let the present back in. Then my mother’s mother showed up. I started to dream and think about this woman whom I had barely known in life, and who has been dead since 1989. My grandmother was an artist, a portrait painter who earned her living by her brush. She was born in 1900 and lived through the flu pandemic of 1918–22. Two other women born in 1900 also began to preoccupy me: French writer Nathalie Sarraute and American actress, opera singer and politician Helen Gahagan Douglas. I was reading Sarraute’s memoir, Enfance (Childhood), and researching the life of Douglas toward writing a libretto. I had pitched the idea of an opera about Douglas to composer and UMaine professor Beth Wiemann. In June, she reached out about the opportunity to apply for a grant to develop a new work. The Helen Gahagan Douglas project moved to the top of my list.

Thoughts about these three women began to intermingle and take shape in my creative unconscious. Then one day, in mid-July, I was seized by a poem. A poem about shopping at Hannaford during COVID-19, but not only. Against an account of the bizarre and exasperating experience of grocery shopping during the pandemic, the poem interweaves snapshots of my grandmother, Sarraute and Douglas. Their lives and the challenges they faced work to temper our contemporary moment. I titled the poem, which turned out quite long, “1900.”

Excerpt from ‘1900’

Susan Camp

ADJUNCT ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ART

As we all try to navigate what is happening in this difficult and politically charged period of time, I have been fortunate to have a farm and woodlot to work on and with. For many years, a primary focus in my practice has been utilizing natural, biodegradable materials; keeping the environmental footprint of my artistic production as small as possible. Conceptually, my work focuses on our relationships with other species, the impact of agribusiness, food production and availability, and the marketing of “natural” products. In this work, I have collaborated with other species, including drosophila, gourds and mold. Most of this work involves constraining or manipulating these other species in environments of my creation.

of scarred trees.

What I notice in my approach to my work during the pandemic is an increased willingness to slow down, observe and listen to what other species are showing me without the need to exert any control on their growth patterns. COVID–19 and the co-existing political turmoil have posited questions of attention: are we really being observant or simply reacting? This has fomented a desire to be less analytical and more playful in my approach. I feel very much like I did as a child, wandering around in the woods, stopping for as long as I want to observe what I see, and finding ways to record those observations with the hope of eventually sharing the artifacts of my experience.

I have been building on my investigations of interspecies entanglements by creating “skins” made from natural latex casts of trees in my woodlot that were scarred by logging equipment over 40 years ago. These irregularities (where the trees have been forced to change their growth patterns) document the coercive forces that surround these organisms and the resilience in their adaptations to the changed environment. The impressions of the natural forms serve as visual metaphors for the damage we endure and inflict (both visible and hidden) and the beauty of resilience.

Scars, visible or not, make us who we are, and these amazingly nuanced casts reveal decades of ductility as the trees responded to trauma. In our culture, we often disdain the irregular — the scars and disfigurement that can accompany trauma, age and the passage of time. The bark of the trees, much like human skin, is more than a protective surface, but also a monument to experiences, heritage and history.

Beth Wieman

PROFESSOR OF COMPOSITION, CLARINET AND MUSIC THEORY

My experience with the beginning of the pandemic was different from that of my UMaine colleagues. I was on sabbatical, already working on independent projects, sometimes in relative seclusion, for most of the 2020–21 academic year. I had received artist-residency support from several foundations, and so was using those opportunities to focus on composing, with some concertizing and short-term teaching in between those residencies.

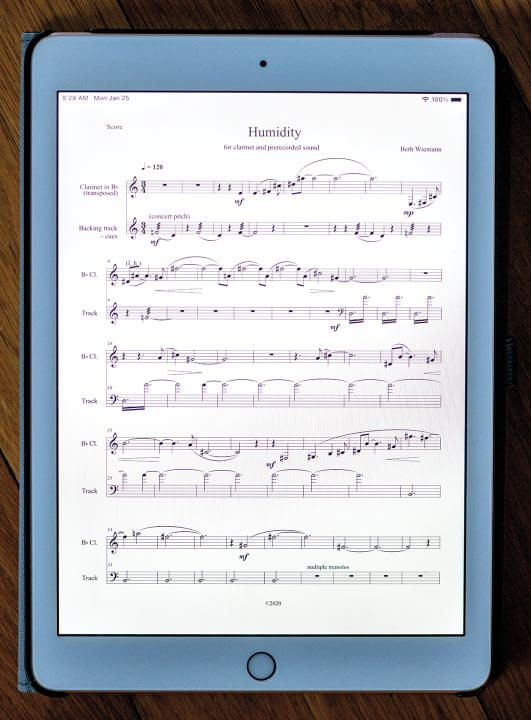

Electronics” 2020, by Beth Wiemann

After early March 2020, obviously all public musical things got postponed or canceled — my expected travel to performances and school visits included. I continued working on pieces that had, at least in theory, deadlines: one for Guerilla Opera and one for the Byrne:Kozar:Duo. Composing these pieces helped me stay focused in spite of all the constant news updates. Both had involving subject matter: for the opera, the real-life story of Rose Standish Nichols, Bostonian suffragette and peace activist; and for the duo, three early poems by Marianne Moore set as a cycle of songs. The song cycle had a test run during a virtual festival this past summer, with the real premiere still TBA. The opera is now into a second draft for an eventual 2021 premiere, and some of the revisions are being made with the thought of performances needing to be livestreamed rather than with an in-person audience.

Other online presentations this summer were more specifically COVID-inspired, like the Art of Virus Project. Invited composers wrote pieces based on a provided theme (or virus), and then invited two other colleagues to write pieces based on a mutation of that theme. My piece, “Masks,” was described by the composer who invited me as “creepy” — accurate, given the visuals I included along with the electronic sound. To date, I’ve only completed two small works in direct response to the pandemic, one creepy and one attempt at a comic scene. I think the creepy one came out better.

Gregory Howard

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

When I think of what it means to be a writer, an artist, in the midst of this pandemic, which, as of this writing, has killed over 200,000 Americans, a number that surpasses the American dead in the Vietnam War, the Korean War and the First World War combined, a number that, as of this writing, will, it seems, continue to grow, and perhaps overtake the number of American dead from World War II, that beginning of the so-called American century, the last century, that lauded and reified event (it’s always war that is lauded and reified for its sacrifice; it is action and death, but not restraint, not consideration, not passivity, which is what our moment asks of us) — when I think of what it means to be an artist or a writer, I have thought of the catalogue, the diary, the record.

Before COVID-19 (or they say in the discourse, in the before times), I was working on a novel that uses the folktale “The Pied Piper of Hamlin” to think about grief, greed, capitalism, power, and how the culture seems, Cronos-like, intent on eating its own children. In addition, I have also kept a document open, an ongoing journal — this one about COVID-19, yes, but in particular about my father, who in March 2020, when the lockdown took hold, began a course of intense chemotherapy for aggressive prostate cancer, and who, this past month, on the advice of his doctors, decided to stop chemo and move to palliative care. I ask myself, the page: what does it mean to mourn from distance? To long to visit the ill, the dying — and, by selfishness and stupidity — be kept from the solace of intimacy?

Art doesn’t change anything, or at least not much, it seems to me. But if art can’t change our material circumstances, it can revivify. It can channel our courage and our rage. It can offer consolation and inspiration, necessary energies as we endeavor to do the difficult work of changing the world, trying to create a place where 200,000 dead can be mourned properly, a place where such death born from callousness, ignorance, greed can never happen again — the kind of work that will truly honor the dead.