Whenever there are reports of a new virus on the planet, University of Maine virologist Melissa Maginnis is listening. And the last weeks of 2019 were no exception. She was familiar with other coronavirus outbreaks — SARS and MERS — that have occurred in the past 20 years, largely limited to Asia. They seemed to be similar to the onset of the coronavirus characterized as novel — COVID-19. In January 2020, Maginnis started talking about this new virus in her graduate virology course at the University of Maine. It was a teachable moment. Until it became so much more.

Over the years, UMaine microbiologist Robert Wheeler also has watched SARS and MERS, plus Zika and Ebola — epidemics that, ultimately, had been brought under control. But COVID-19 was different.

He clearly remembers when his concern became a call to action. He was in San Diego in late February to participate in a four-day National Institutes of Health study section on immunity with a number of other infectious disease researchers. On the second day, he looked around the meeting room and thought: “We should really be going back to our institutions and doing all that we can to study this coronavirus.”

He was soon on a plane back to Maine. But before returning to his UMaine research lab, he had to spend two weeks in self-quarantine, wondering if he had contracted COVID-19, weeks ahead of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring a pandemic.

The UMS Science Advisory Board was formed to stay fully abreast of fast-breaking scientific and medical developments in areas relevant for universities and the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccine development, diagnostic and serology testing, antiviral treatments, transmission mitigation and contact tracing.

For UMaine biomedical engineer Caitlin Howell, her community connections were buzzing early last spring. She was hearing that hospitals in Maine were getting nervous about their ability to disinfect their personal protective equipment. They were looking for any information they could find on safe and effective sterilization methods.

Howell and her students quickly realized that there were a lot of knowledge gaps around what was likely to be effective and what might be dangerous. They set about helping Maine health care teams access and understand the latest information possible from the most rigorous scientific sources.

Neurobiologist Kristy Townsend was monitoring the rapidly evolving medical literature. When Bangor Public Health needed help distilling the latest findings to inform health and safety guidance, and had specific questions, Townsend and the students in her lab sprang into action, producing science and medicine update sheets from March to July.

Townsend also was talking about the need to mobilize UMaine’s expertise and research infrastructure to build COVID-19 testing capacity, planting the seed for forming an advisory committee.

UMaine President Joan Ferrini-Mundy saw the big picture. The former chief operating officer of the National Science Foundation was a year and a half into her position as the president of the state’s research university. With preparation in mathematics and education, and as a nationally recognized STEM education expert and thought leader who values science and evidence-based practice, she watched WHO declare a pandemic and knew what UMaine had to do — put its breadth and depth to work to help Maine in this time of crisis.

University of Maine System (UMS) Chancellor Dannel Malloy, former governor of Connecticut and no stranger to big-picture public health challenges, established a UMS Science Advisory Board (SAB), chaired by Ferrini-Mundy. She tapped UMaine faculty who were already on the front lines — Townsend, Maginnis, Howell and Wheeler. They were joined by Sara Huston, chronic disease epidemiologist at the University of Southern Maine.

The UMS Science Advisory Board was formed to stay fully abreast of fast-breaking scientific and medical developments in areas relevant for universities and the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccine development, diagnostic and serology testing, antiviral treatments, transmission mitigation and contact tracing. After UMaine pivoted in the spring semester to fully remote learning, SAB’s evidence-based work was key to the UMS 2020 Safe Return Planning Committee, providing science-informed approaches to safely welcome students, faculty, staff and the public back to Maine public universities in the fall.

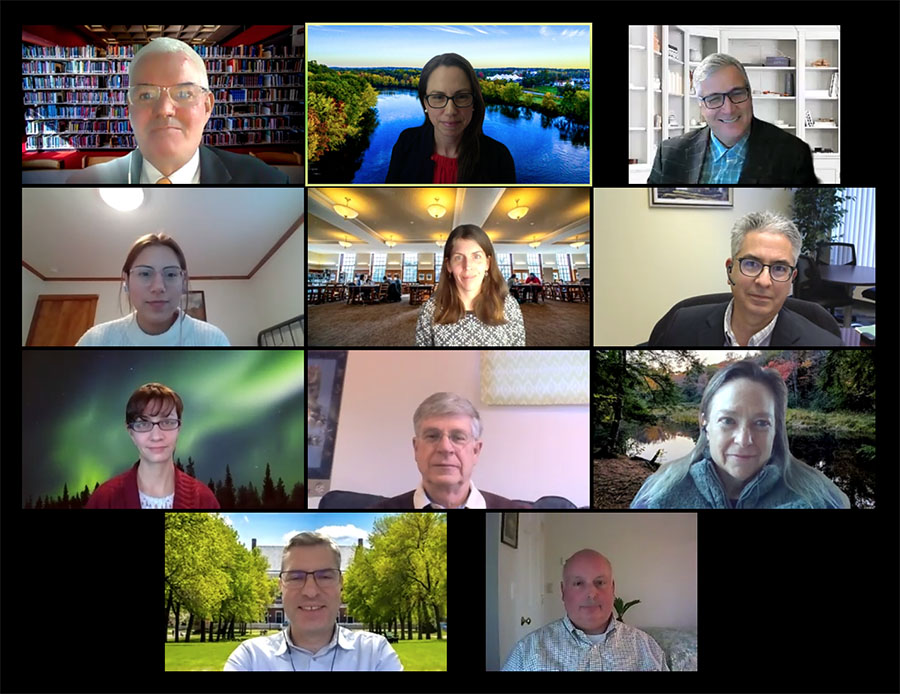

UMS Science Advisory Board members provide guidance on the latest COVID-19 health and safety best practices to a wide range of constituents — from university students through public health education campaigns to presentations to Maine legislators, and state and national health and science groups. “Being able to communicate public health information across broad audiences, including translating science to a lay audience, is really important,” says SAB lead Melissa Maginnis. Ongoing SAB communication ranges from scheduled Zoom meetings like the one pictured here with University of Maine System leaders to updates on campus-based wastewater testing analysis (first image). There is even a student- focused public health campaign video starring Maginnis and UMaine’s mascot (last image).

SAB members have provided scientific guidance on the latest COVID-19 health and safety best practices to a wide range of constituents — from university students through public health education campaigns to presentations to Maine legislators, and state and national health and science groups.

At the state’s largest university, which also has offices and facilities statewide, scientific guidance informed the COVID-19 Response Team established in the Emergency Operations Center (EOC). UMaine staff who are members of the COVID-19 Response Team and UMaine’s EOC, working in collaboration with the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, have been the boots on the ground in the pandemic battle.

They are the unsung heroes working nonstop to ensure a safe return for UMaine students and employees, all doing COVID-19 response — from expanded facilities cleaning to care management and contact tracing and on-campus testing — in addition to their UMaine jobs, and meeting professional and personal challenges related to the pandemic.

All are in it together, demonstrating a primary example of Maine’s public research, land-sea-space grant university mission in action during the pandemic.

“Research and Extension faculty, staff and students turned their attention to help solve very real problems for Maine — solutions that will scale,” says Ferrini-Mundy. “This response is possible by having the infrastructure in place — facilities, people and networks. UMaine, like other land grant universities, has responded to state needs for over 150 years, perhaps no more so than during this public health crisis. In doing so, this positions us for our next phases of work and impact, all of which will be informed by what we’re doing now as a public research institution.”

In spring 2020, the challenges of the unknown were daunting: stay-at-home orders, no robust testing available, uncertainty of just how the virus was transmitted, and measures needed in health care settings to help reduce the suffering.

The Science Advisory Board members were teaching and mentoring students in their labs, and conducting their own research. Most have young families at home. Like so many other members of the UMaine community, they heeded the call to do what they could in response to the pandemic.

“We were in a scurry the last week before spring break to figure out how many more classes we’d have in person, when and how we would go remote, how would that work,” Townsend says. “Looking back now (this is around March 13, 2020), it was incredible, in real time, to introduce the students to something that would then, over the last year, hugely evolve in terms of our scientific understanding and the available data that we had about this virus and the disease that it caused.”

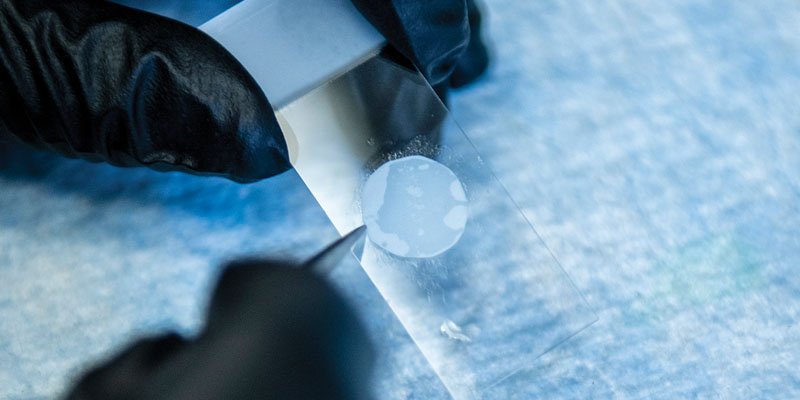

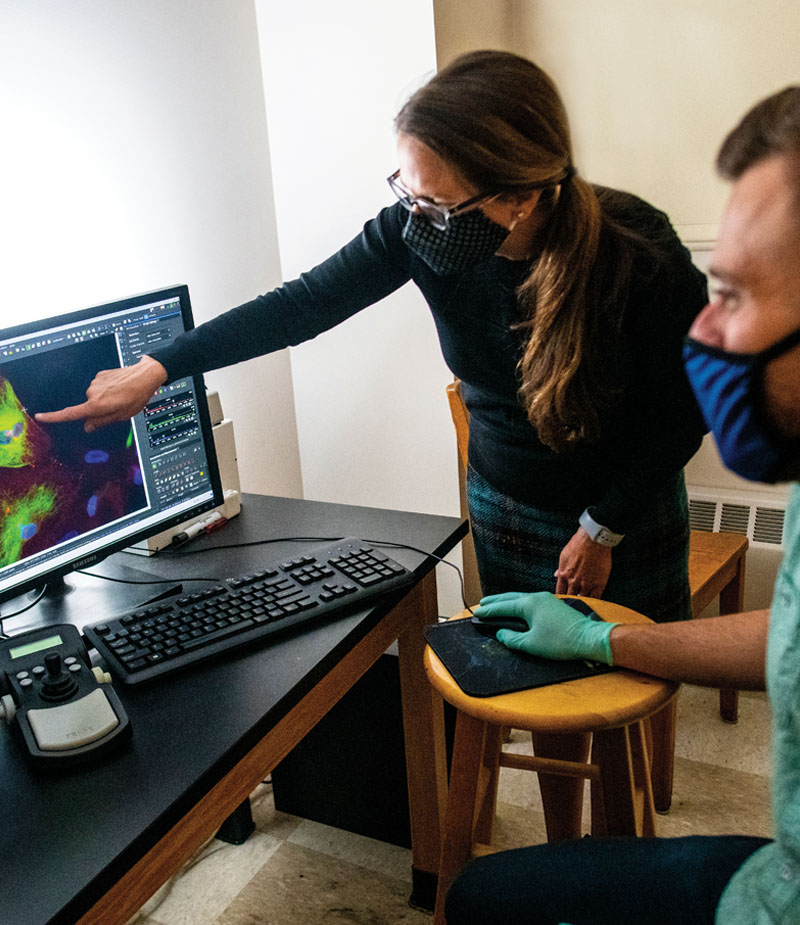

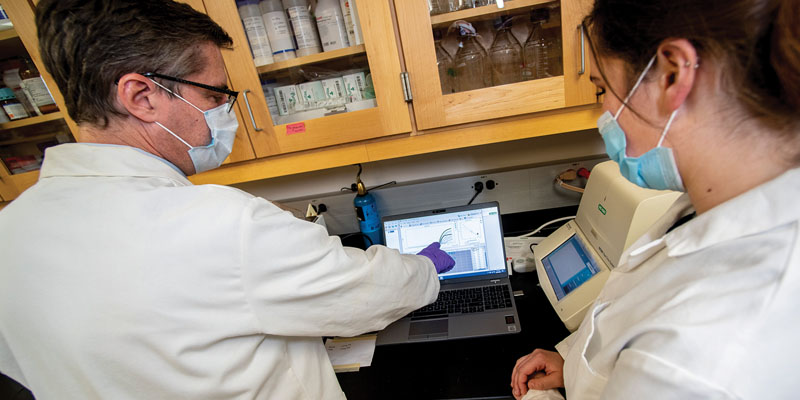

In their laboratories on campus, Science Advisory Board members Caitlin Howell, Melissa Maginnis and Robert Wheeler research different but interrelated areas, all involving undergraduate and graduate students. Howell focuses on creating and testing new bio‑inspired materials, developing nontoxic strategies to control the interactions of biomolecules, microorganisms and cells with surfaces. Currently, she is leading National Science Foundation-funded research to develop a membrane to capture airborne particles, including COVID-19 viruses, for analysis. Maginnis’ research focuses on how viruses like JC polyomavirus infect cells to cause disease. Her broad background in virology was the foundation for her current work in SARS‑CoV‑2. Wheeler’s research focuses on understanding how the human immune system interacts with a human pathogen; in particular, the fungus Candida albicans. His study of microbes and their interaction with the human host, experience with mouse and zebrafish models of disease, and understanding of human clinical studies were important foundations for SAB.

Every hour, hundreds of emails were flying among SAB members as they shared and discussed scientific papers and the latest COVID-19 updates. The team got organized with the Slack app. The search for the latest information is “going on all the time, every day, all day long,” Maginnis says.

“Sometimes people are posting things at 1 in the morning. Sometimes it’s 5 in the morning. There’s usually always one of us active on Slack,” Maginnis says.

Trying to corral the latest COVID-19 information and make sense of it can really take over your life, Wheeler admits. “There are quite a few days where more than half of my waking hours are associated with either taking in and processing information or communicating that information out and discussing it.”

In April 2020, armed with the latest updates available from their disciplines, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO and other sources, SAB members began meeting via Zoom with university leadership and teams responsible for pandemic response for UMS campuses.

Questions about how to have a safe return to university campuses in the fall were complicated by the ever-evolving information about coronavirus. SAB shared the latest information about transmission and treatment, then testing and possible vaccines.

“One of the most pivotal moments was when we developed our testing partnership with ConvenientMD and The Jackson Laboratory,” Maginnis says. “There was a lot of work and research that went into developing these testing partnerships. When we determined that we could do robust testing and that we could do entry‑level testing, that meant that our universities could choose to provide in‑person instruction and have students reside on our campuses.”

Testing partners for the fall semester also included Vault Health. To meet the rising demands of the pandemic in the 2021 spring semester, UMS partnered with Shield T3 to bring a mobile lab to the UMaine campus, which provides weekly saliva testing for the entire in-person population across the University of Maine System.

Initially, Maginnis focused on the latest information on treatments and vaccines, Townsend and Wheeler on testing, Howell on transmission, and Huston on public health epidemiology. Their roles and responsibilities evolved with the pandemic. As the months went on, other experts contributed their talents, including statistician Bill Halteman. In August, Townsend moved her lab to The Ohio State University, and continued to share information resources with SAB.

After UMaine pivoted in the spring semester to fully remote learning, SAB’s evidence-based work was key to the UMS 2020 Safe Return Planning Committee, providing science-informed approaches to safely welcome students, faculty, staff and the public back to Maine public universities in the fall. That included COVID-19 testing before students moved into their residence halls; the Black Bears Care plan for all UMaine community members to protect themselves, others and the community; the health and safety guidance indoors and out, requiring face coverings, social distancing, frequent hand washing and campus-based COVID-19 testing.

Asymptomatic testing and wastewater analysis are components of the campus and community COVID-19 monitoring strategy. “The wastewater testing group has been a wonderful collaborative project of folks in facilities, folks in procurement, undergraduate scientists who have been working in my lab to do the actual wastewater testing under my supervision and scientists who are working together with various disciplines from engineering to infectious disease,” Wheeler says. “I’ve always known that the University of Maine is a collaborative place.”

What is a typical day in the life of an SAB member who is also conducting research, teaching and having a home life? “My life shifted dramatically,” Townsend says. “I set up a home office where I was sitting and working with my kids in the other room who weren’t in school. I was hoping, unless I heard a loud noise, that they were entertaining themselves okay — they actually did a great job. Many late nights, little sleep and a huge sense of responsibility.”

From the start, President Ferrini‑Mundy said she would like to see science be an important part of this, Howell says. “She recognized that that was a critical part of keeping our community safe. I’m very happy that our president had the foresight to recognize this so far ahead of the game and put it in place so that it can be doing what it’s doing now.

“These are rock star researchers and I’m so grateful every day to be able to work with them,” Howell says. “They’re searching for solutions to problems. I think that it’s that dedication and synergy, that collaboration, that has made it possible for us to get to where we are today as a Science Advisory Board.”

Research and Extension faculty, staff and students turned their attention to help solve very real problems for Maine — solutions that will scale. This response is possible by having the infrastructure in place — facilities, people and networks. UMaine, like other land grant universities, has responded to state needs for over 150 years, perhaps no more so than during this public health crisis.”

PRESIDENT JOAN FERRINI-MUNDY

The three UMaine researchers with laboratories on campus have expertise in different but interrelated areas.

Maginnis’ research focuses on how viruses like JC polyomavirus infect cells to cause disease. Her broad background in virology was the foundation for her current work in SARS‑CoV‑2.

“We view (coronavirus) as something that we need to understand and not fear,” Maginnis says. “I think that that’s true in science in general. If we can understand the basic biology of the virus, how the virus is transmitted, how it infects cells, and how it’s activating the immune response, then we can develop therapeutics that can help to target those virus‑host cell interactions to either activate or dampen the immune response.”

Maginnis’ interest in studying virology stems from her grandfather’s experience with polio. The virus left him paralyzed for a year. He was 21.

“I stay in the field,” she says, “because I want to contribute to understanding human disease so that we can help relieve human disease and suffering.”

Maginnis teaches UMaine undergraduate and graduate virology courses, and leads a research lab with four Ph.D. students and eight undergraduates. Last spring in her graduate virology course, Maginnis and her students were watching the novel coronavirus outbreak unfold. “By all definitions, it was a pandemic, but it had not been called a pandemic by the World Health Organization yet. We were saying, ‘You’ve got to call it.’ Two days later, we walked into class, and it was declared a pandemic.”

The most asked question by her virology students: why don’t people get it? Why don’t people understand that if they just wear a face covering and follow the public health measures, that we would be in a much better position than we are now?

“That’s another important learning experience through this pandemic — how people critically think through information and how we provide that information to the public so that it’s accessible in a way for people to understand it,” Maginnis says.

“Being able to communicate public health information across broad audiences, including translating science to a lay audience, is really important and something that we’re training our students to do,” says Maginnis.

Starting in February, a Shield T3 mobile testing laboratory based at UMaine processed the COVID-19 tests for students and employees learning and working on University of Maine System campuses statewide.

Howell’s research focuses on creating and testing new bio‑inspired materials. Her Biointerface and Biomimetics Engineering Lab develops nontoxic strategies to control the interactions of biomolecules, microorganisms and cells with surfaces. The results are new approaches to stopping infections in implantable medical devices that don’t require antibiotics, or environmentally friendly methods to stop algae or other marine organisms from sticking to boat hulls, among other applications.

She is joined in this work by three Ph.D. students, three master’s students and six undergraduates, and integrates the results into her courses on bio-inspired engineering and moving biomedical engineering technology from the lab to the market.

Last year, the National Science Foundation funded research led by Howell, in collaboration with Maginnis and University of Massachusetts Amherst chemical engineer Jessica Schiffman, to develop a membrane to capture airborne particles, including COVID-19 viruses, for analysis. The long‑term goal is to have an air filtration system deployed for continuous monitoring in places that are particularly high risk for a widespread outbreak — hospitals, elder care facilities, travel hubs, schools.

“What lights the spark for me is being able to create things that can help people, not just doing science in a lab,” Howell says. “I am curious, I want to know, but I also want to know that I am working on something that can help make people’s lives easier. Biomedical engineering is a fabulous way to do that.”

Howell encourages her students to be innovative and to ask questions. In the pandemic, she has told them “to be curious, to look deeper into information and try to understand what is going on from the global perspective.”

“If there’s anything that we’ve learned from this pandemic, it’s that our guesses can often be wrong because there are factors that we don’t understand,” Howell says.

For two decades, Wheeler has dedicated his research to understanding how the human immune system interacts with a human pathogen; in particular, the fungus Candida albicans. The microbe lives in our gastrointestinal tract and normally doesn’t cause any harm. But in immunocompromised people, it can cause a lethal, life‑threatening disease. The drug-resistant fungus has proved particularly lethal in hospital settings.

Wheeler’s study of microbes and their interaction with the human host, experience with mouse and zebrafish models of disease, and understanding of human clinical studies were important foundations for SAB.

“There’s a combination of fascination and a real horror at how successful it has been and how it’s uprooted my life, my family’s life, my colleagues’ lives and the whole world,” says Wheeler, an investigator in the pathogenesis of infectious disease by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

His interest in infectious diseases was sparked by UMaine alumnus Stanley Falkow, who went on to be a researcher at Stanford University, where Wheeler did his Ph.D. Today, Wheeler teaches courses in immunology and infectious disease at UMaine, and has 14 undergraduate and graduate students in his lab.

“My students have been amazing throughout the pandemic. They got into this field because they’re interested in helping to prevent and treat human health issues. There’s a real strong altruistic component to infectious disease research,” he says.

“A research university attracts people who want to help, contribute to science, and serve the university and strengthen partnerships in the community,” Maginnis says. “The important thing is making sure that that infrastructure is strong so that we can respond in times of crisis, and also in times when we’re generating new knowledge and moving the field of science forward.”

The researchers say there have been some silver linings to the pandemic, among them: the opportunity to collaborate across the UMaine community, statewide and beyond, and giving the public a better appreciation for the importance of science.

“Having that scientific expertise on campus, just the same as having expertise in history, in literature, in anthropology, and all of the different components of a research institution like the University of Maine, has such a tremendous forward‑thinking component to it,” Wheeler says.

“When we look around at what other state universities have done with the pandemic, that role has been quite variable. What we have done is really exemplary,” he says.

Howell says she has been gratified to see the scientific community have the opportunity to show what it is capable of and what it can do for the larger public.

“We have been able to demonstrate that we are here to help, that we care,” says Howell, a member of the Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering that also had faculty, students and staff mobilized in numerous initiatives to aid Maine’s health care community. “We’re doing our best to get quality information that is as free from bias as possible because we recognize how important that is to our communities.”

“Scientists seek the truth,” Maginnis says. “They contribute new knowledge, enhance our understanding and share it for the greater good to improve the lives of people around them. It’s what we do.”