In 2008, older adults in the United States ages 65 and older numbered 38.8 million. In just 10 years, that number swelled to 52.4 million — a 35% increase — and this cohort is expected to grow another 54% by 2040 to 80.8 million, sweeping in the last of the baby boomers born by 1964. And the climb will continue, with an estimated 94.7 million older adults in 2060, a 17% increase over 2040.

Certainly, that post-world-war baby boom is a key factor in these increases, but the U.S. also is seeing life expectancy increase as new health care technologies emerge and personal care improves. A child born in 1900 had a life expectancy of just 47.3 years. Compare that to 2018 when a newborn’s life expectancy had risen to 78.7 years.

Today, the percentage of older adults is 16% of the U.S. population, or about one in six. In Maine, the percentage is 21%, or more than one in five Mainers. Maine is one of just three states at 20% or more. (Florida is also 21% and West Virginia is at 20%.) The “oldest state” designation comes from identifying the median age of a state’s population. The median age of a Maine resident is 45.0, the next closest is New Hampshire at 43.1. The national median for all states is 38.2 years of age.

Longtime Mainers and even those who have immigrated to the state during their lives find great rewards in making this their home. There is the pristine natural beauty that defines the state — the extraordinary coast, mountains and waterways, opportunities for outdoor adventure and exploration. The relative quiet of the small towns and open spaces appeals to many. And then there is the lifestyle that may be difficult to define, but is summed up in Maine’s slogan: the way life should be. This speaks to a work/life balance that others envy. There is that sense of “everyone in Maine knows each other” that pervades daily interactions. And, as a result, one understands the helping inclinations of rural living. Life in Maine has been characterized as perhaps simpler and more personalized than one might find in other parts of the country, even other parts of New England. It is easy to see why rural living in Maine is a strong attraction for elders.

Elders coping in Maine’s rural environment

Maine is the most rural state in the U.S. with 61.3% of the population living in communities of 2,500 people or fewer. That fact, coupled with the high percentage of older adults in Maine, presents daunting challenges, now and into the future. Reflecting on the center’s work over two decades, Kaye set out to catalog those challenges with the help of 113 other contributors. The Handbook of Rural Aging was published in 2021. At 471 pages, covering 79 issues pertinent to elders living in rural communities across the country, the book is a major resource to providing insight into the lives of our older citizens.

Photographs by Elyse Klysa, David Levy, Angie Devenney

Consider just a few of the struggles that perplex our elder society —

Health care: Does Maine have the capacity to care for its ever-growing older population living in largely rural areas? Significant health issues require specialized expertise. Gerontologists, gerontological nurses and pharmacists, and other medical practitioners are at a premium nationwide, as well as in Maine. As the older adult population grows, those scarcities are exacerbated. Hospitals, retirement and assisted-living communities, home and health care organizations’ capacities are strained. Particularly overburdened is the caregiver.

Over the past 18 months, we have been starkly reminded of another huge pandemic beyond COVID-19, that of isolation and loneliness that many, many older adults encounter.

“Caregivers in rural areas are more often reporting that they had no choice in taking on care and also find the help they provide more difficult,” writes Kaye in The Handbook of Rural Aging. “Furthermore, while they are typically working in an hourly job in addition to performing their caregiving duties, they are more likely than urban caregivers to report financial strain resulting in delaying plans for saving, assuming more debt, not paying bills or doing so after they are due, and borrowing money from family and friends. They are less likely to have health insurance and more likely to have trouble managing their own health than urban caregivers.“

Focusing on real aging

FOCUS ON Real Aging in Maine (F.R.A.M.E.) celebrates and promotes positive, realistic images of the diverse aging experience in Maine. It launched in 2021 with a statewide photography contest, sponsored by the Maine Gerontological Society and the University of Maine Center on Aging in collaboration with the Maine Community Foundation and the Elder Abuse Institute of Maine. Lisa White, a UMaine social work graduate student working in the university’s Center on Aging, helped organize F.R.A.M.E. with the support of Patricia Oh, the center program manager.

The photo contest attracted 82 entries from amateur and professional photographers of people in Maine ages 50 and older. Prizes were awarded to three amateur photographers and three professional photographers. Six Maine amateur and professional photographers judged the respective entries. In addition, there was one People’s Choice Award.

The goal was to bring a more positive perspective to older Mainers during the COVID-19 pandemic, which marginalized elder adults, according to the organizers. F.R.A.M.E. responded to the need for images showing the reality of aging in Maine, especially in our rural communities.

“The UMaine Center on Aging celebrates the public health success of Mainers living longer, healthier lives,” says director Lenard Kaye. “We are all aging. However, it is hard to find free-use photos of older people enjoying life. With help from our partners, the Maine Community Foundation and the Elder Abuse Institute of Maine, we have created a library of photos that show older people doing the things we all do — working, volunteering, and having fun with family and friends. Our hope is that when nonprofits and local organizations start to use these photos to depict aging, we will all contribute to a more positive view of aging.

“These images are terrific and serve to smash negative aging stereotypes.”

F.R.A.M.E. images are in a new Maine Gerontological Society online library. The relevant, age-friendly photos are available free of charge for limited noncommercial use on websites and in other publications by individuals and nonprofit organizations.

Transportation: Older adults frequently struggle with access to the services they require. In a rural setting, where people and services are spread out, and especially if the elder no longer drives, every trip — doctors’ appointments, grocery shopping, religious worship or cultural events — can be complicated. Public transportation is practically nonexistent in most rural areas, taxis or shared-ride services can be expensive, and elders’ families have frequently migrated to other areas for new opportunities.

Isolation and loneliness: Over the past 18 months, we have been starkly reminded of another huge pandemic beyond COVID-19, that of isolation and loneliness that many, many older adults encounter. This debilitating, life-threatening condition was brought strongly into focus in 2020 and 2021, but existed prior to the pandemic and will undoubtedly continue post-COVID-19 crisis. Isolation and loneliness are not conditions exclusive to rural aging, but often made more prevalent by how people are spread out and how families have dispersed.

“Addressing social isolation as a major threat to the health and well-being of older adults in rural communities will require a multifaceted approach,” according to Boston College professor emeritus James Lubben and University of Iowa professor Mercedes Bern-Klug, both in social work, writing in the The Handbook of Rural Aging. “Rural communities need to be educated regarding the serious consequences of social isolation. Governments and various community organizations need to develop policies and programs to address the problem. Health and social service personnel need to be better trained and have available appropriate practice protocols to identify both those older adults at risk and those who are already socially isolated. Finally, rural older adults need to attend to this important health problem in their own personal lives.”

Digital access: Another major, multifaceted obstacle in Maine is keeping older adults connected and informed. In many parts of the state, broadband service is simply unavailable. If access exists, many cannot afford the service. Also, many older adults have been reluctant to embrace the technologies enough to learn to use them. There are tremendous benefits to equipping our elders with new technologies, Kaye says, including helping to address health care shortages with telehealth applications, and reducing isolation and loneliness concerns through online visual communications.

Mental health: Reporting in the handbook, Jennifer Crittenden presents this sobering reality: “The impacts of mental health and substance use disorders reverberate throughout rural communities and have significant implications for older adults and their families,” writes the UMaine assistant professor of social work and Center on Aging associate director.

Age-related lessons from the pandemic

AT THIS TIME, there can be no discussion of rural aging without addressing the impact that COVID-19 has had on the older adult population since March 2020. All of the challenges that older adults experience in a rural environment have simply been intensified due to COVID-19, like food insecurity or access to services. From the start of the pandemic, impacts older adults have experienced include greater isolation and loneliness, a reduction in available services and a huge loss of mobility.

AT THIS TIME, there can be no discussion of rural aging without addressing the impact that COVID-19 has had on the older adult population since March 2020. All of the challenges that older adults experience in a rural environment have simply been intensified due to COVID-19, like food insecurity or access to services. From the start of the pandemic, impacts older adults have experienced include greater isolation and loneliness, a reduction in available services and a huge loss of mobility.

According to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of Maine COVID-19 cases of older adults from March 2020 to July 30, 2021 approximately correlates with the total population: 13,879 of adults 60 and older compared to 70,261 total cases or 19.75%. But that same age group represents 92.2% of deaths due to COVID-19 (830 of 899 total deaths).

“(COVID-19) has exposed the best and worst of aging in Maine,” says Lenard Kaye, director of the University of Maine Center on Aging. “At its worst, it has proven fatal to many older adults, and disproportionately compared to others, especially those in long-term care. Our long-term care system was not prepared for such a public health crisis. The system could not respond quickly to the needs of older adults, such as getting the personal protective equipment needed, and locating scarce resources which were directed initially to acute care, not chronic care. Nursing homes were the last to get help, last to get training, last to get masks and everything else needed to protect our older adults.

“On the positive side, it taught us how critical it is that older adults get on the digital bandwagon to take advantage of available technology because it can be a lifesaver in protecting them from becoming isolated and lonely. It taught us how important social networks are in making connections for older adults such that they remain part of daily life. And it has created new approaches that we’re taking in reaching out to older adults. We want them to take advantage of technologies that support their health and well-being.”

Even prior to the pandemic, on April 27, 2017, Kaye presented testimony before the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging documenting the potentially lethal consequences of social isolation and loneliness.

“For older adults residing in rural communities and those who serve them, lessons learned center around being more aware in the future of the consequences that can be expected of pandemics and other public health emergencies for rural-residing older adults, their families, and community service and health care providers. Also learned is the imperative that policymakers, providers, and older adults themselves plan ahead more systematically and implement both common sense and creative strategies for ensuring that older rural Americans stay connected to others in their communities at the same time that the risk of increased isolation, loneliness and anxiety during challenging times is minimized.”

“Rural areas have shouldered much of the burden of the opioid epidemic, which affects residents across the life span with rural residents having a greater likelihood of experiencing an overdose. While substance use disorder prevalence is similar across rural and urban settings, data suggest that the use of alcohol is higher in rural areas and the impacts of opioid use are more significant in rural regions. Furthermore, close to one in four rural older adults is considered at-risk for depression and suicide.”

Considering just these few major concerns of many, how can our Maine older adults navigate their lives in a healthy and productive manner?

Support to thrive

As a state-funded institution, the University of Maine works to support all the people of Maine. That includes the 21% who are 65 and older. Throughout its history, the focus of the Center on Aging has been constant: to support the needs of older adults, Kaye says.

“Our research efforts have shifted in that time from studying diseases and the problems of an aging population to more progressive themes, including health care, technological advances, and productive aging — that is, positive dimensions of aging,” Kaye says. “We have always remained open to new opportunities and because we were small, we could turn on a dime. We have always worked with communities, local agencies, foundations and smaller community organizations.”

The Center on Aging provides the greatest share of UMaine elder services and programs, and is involved in multiple aging initiatives statewide. It maintains a partnership with the University of New England called AgingME Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Project and partners with the five Maine Area Agencies on Aging. In addition, the center sponsors or is affiliated with numerous programs focused on interacting directly with the state’s older adults — Senior Companions, Retired Senior Volunteer Program, Senior College and more.

The center maintains a 5,000-subscriber monthly newsletter, keeping the community informed of initiatives, activities and resources statewide. Older adults can register for the Adult Research Registry, created by the Center on Aging to assist researchers by serving as “citizen scientists” and participating in pertinent research studies.

Individuals who work with elders can earn an Interprofessional Graduate Certificate in Gerontology through the Center on Aging, focused on enhancing understanding of the specific needs of older adults.

The center is working in partnership with The Cedars, a continuing care retirement community in Portland, in development of Designation of Excellence in Person-Centered Long-Term Care to identify high-quality long-term care communities across the nation. Another project will determine probable acceptance of a heart-assisting device (left ventricular assist device or LVAD) that keeps people alive. With University of Southern Maine as the lead, they have simulated the operation in a mock LVAD to predict a patient’s acceptance of the device prior to making a major commitment.

Every October, the center conducts a one-day Clinical Geriatrics Colloquium for participants to learn the latest information and trends. Last year, the focus of the 16th annual colloquium was advancing anti-racism, diversity, equity and inclusion in older adult health care.

Another major focus currently is age-friendly communities. Maine has among the highest number of such communities of any state in the U.S. — an eighth of all designated age-friendly communities. The Center on Aging has a contract with AARP to deliver training on implementing age-friendly communities nationwide.

The Center on Aging is committed to ensuring positive outcomes related to Maine’s older adult population growth. “Adults are perceived as carrying with them increasing measures of wisdom, expertise and capacity into their later years. We are now talking about ways in which these personal assets can be harnessed and applied to benefit families, organizations, and communities,” noted Kaye in 2015, writing in Maine Policy Review.

Six years later, Kaye is more determined than ever to enable and raise awareness of the fact that “older adults are the key to the solution.”

“They have yet to contribute all that they can,” he says. “Today they are more mobile, more active, and they are living healthier and longer lives than ever before. They can remain in the workforce, work part-time, volunteer, develop second or third ‘acts.’ There are so many new approaches to enable older adults to live fulfilling lives.”

Crittenden couldn’t agree more. In “Never too old to lead,” a Maine Policy Review article, Crittenden and Lelia DeAndrade, vice president of community impact at Maine Community Foundation, report on older adults who receive training in leadership that they then “apply to team-driven projects, such as improving neighborhood quality, providing voter education, and offering juvenile offender rehabilitation.” The center’s Encorps program, a precursor to age-friendly communities, has been offered to “engage Mainers 50 and older in community-based leadership through volunteer projects,” which might include serving on local committees, boards and town councils; revitalizing and developing downtowns; preserving, protecting and improving public and outdoor areas.

In 2021, Crittenden suggests that ever-increasing use of technology will advance the support of older adults with everything from telehealth solutions, especially in rural areas, to increasing socialization and decreasing isolation as older adults become more comfortable with smart phones, tablets, and other electronics.

Indeed, the age-friendly community model appears to point positively toward the future for rural aging. Its guidelines address several of the challenges for older adults. Each community decides which needs to address with help from a grassroots committee made up of concerned citizens, older adults, nonprofits, town officials; in other words, people who have a shared interest in the vitality and future of their community. Everyone benefits.

“Each rural community is unique,” noted former assistant secretary for aging Kathy Greenlee, writing in Generations. “Rural people have to adapt. They take care of each other. Rural communities figure it out. … Older rural people are at risk for social isolation. But what they have going for them may be a lifetime of community involvement.”

The age-friendly community understands those concepts and opts for a supportive and inclusive environment for all.

Active engagement of

Maine’s older adults

AS OLDER adults live longer and healthier lives, it is critical that they have opportunities to remain vital. Some may choose to continue working, some may embark on new careers, others may take up new hobbies, still others find time to volunteer. The Center on Aging offers engagement programs to help elders remain active.

“We want people to volunteer because it improves health, cognition,

well-being, socialization,” says Jennifer Crittenden, UMaine assistant professor of social work and Center on Aging associate director. “Volunteering has been associated with a lot of health improvements for older adults.”

The Senior Companion Program, an Americorps program administered by the center, enlists volunteers 55 and older to be companions to homebound or isolated adults. These individuals provide support by visiting, sharing information, helping arrange for home maintenance, reading aloud, facilitating time off for caregivers, providing transportation to appointments, or any other tasks that can help that person maintain the highest level of independence.

The Retired & Senior Volunteer Program (RSVP) is another Americorps-funded program, administered by the center since 2003. Nearly 100 RSVP volunteers in Penobscot, Piscataquis, Hancock and Washington counties are paired to projects, such as reading to children in HeadStart programs and child care centers, leading senior wellness activities and helping to fight food insecurity.

In a recent activity, RSVP volunteers worked on a telehealth simulation exercise designed to train nurse practitioner students to work effectively with older patients. “A lot of schools work with what are called ‘standardized patients,’ basically actors who come in and play the patient,” Crittenden says. “But we have these volunteers who’d been doing health and wellness volunteering, but had been sidelined by COVID-19. They were trained to serve as a patient or a caregiver for this simulation.”

Afterward the volunteers were interviewed about their experiences. They reported that they got so much out of it personally, bringing in their own experiences. Crittenden adds that “it taught them about questions they might bring in their own health care visits. The volunteers loved the inter-generational piece of working with the students.”

A new RSVP program, Walking Buddies, connects a volunteer with another older adult to encourage healthy exercise while providing socialization, all in support of healthy living. The objective is to meet and walk two to three times a week for at least six weeks.

Care for Maine’s older adults

A KEY COMPONENT of the University of Maine’s contribution to research on healthy rural aging in Maine is the Cognition Aging Resiliency and Enhancement (CARE) Lab. It is directed by assistant professor of psychology Rebecca MacAulay, whose research focuses on understanding factors that increase risk and resilience to cognitive decline across the adult life span. She and her graduate and undergraduate students in the lab explore intervention approaches to improve wellness from both cognitive and mental health perspectives.

CARE Lab is currently working on two projects that address cognitive function in older adults. One is M-ABLE, the Maine Aging, Behavior, and Learning Enrichment study, focused on brain health and the tools used to measure thinking and memory in older adults. MacAulay’s research team is exploring how technology can improve cognitive assessment and reach underserved populations, and the relationship of gait and cognition impairment in older adults.

The lab’s other project, Maine Understanding Sensory Integration and Cognition (MUSIC) is a study that considers the connection between learning music and improved brain health. The research study explores novel ways to improve cognitive function through learning and playing music — one of the most mentally stimulating activities.

“Often in research we focus on one concern,” MacAulay says. “We often will look at cognitive health. We’ll look at vascular health. We’ll look at depression. My research is really trying to understand the intersections among these things. If you have vascular disease, you’re more likely to have depression and vice versa. For example, we see that over 75% of adults over the age of 65 have multiple chronic conditions.

“We’re really starting to think more about what the individual’s values are, how we honor that and I think that becomes particularly important in rural areas where rural has almost taken on a little bit of a negative connotation because we see the negative health outcomes,” says MacAulay. “There’s just a lot of health and financial disparities in these rural areas. But I think as Mainers, we also know there’s a lot of resilience in our rural communities. We’re a rural state and it’s that kind of grit, so to speak, that makes Maine, Maine.”

Classes to help older adults maintain healthy bodies are offered at the UMaine New Balance Student Fitness Center. They include Fit Over 50, focused on mobility, balance and fitness.

Another form of engagement centers on educational pursuits. Penobscot Valley Senior College, established by the Center on Aging and part of the statewide Maine Senior College Network, offers noncredit courses in six-week sessions for two hours each week for adults age 50 and over. Classes in the arts, natural sciences, history, culture and more provide learning, socialization and intellectual stimulation without tests or grades.

In addition, older adults seeking academic rigor may enroll at the University of Maine with tuition waived for Maine residents who will reach the age of 65 years or older during the semester in which they enroll, who are seeking to take undergraduate university courses for personal enrichment and/or to attain their first undergraduate degree.

Photographs by Lisa DuFault, David Levy, KG Moates

Older adults also have engagement opportunities to be involved in research at UMaine. The Center on Aging maintains a confidential Older Adult Research Registry of more than 200 elders interested in participating in research studies conducted by university faculty. Research projects may focus on older adult health issues, volunteering, testing products or discussing services for older adults. Registrants must be at least 50, interested in taking part in research, and must complete a questionnaire to enroll.

Other opportunities to participate in research may come directly from UMaine researchers. For example, UMaine assistant professor of psychology Rebecca MacAulay conducts several studies focused on cognition, including memory.

“If we want interventions, practices that serve all rural older adults, we need to figure out how to engage them in the research process,” Crittenden says.

One research method that can really engage older adults is participatory action research, Crittenden notes. Instead of researchers recruiting older study participants, in PAR initiatives, local committees may be formed to develop a research plan based on community needs.

While the opportunities for older adults are diverse across the university community, the goals are the same: to enable elders to maintain active, engaged lives to help themselves and to help others. They are in keeping with UMaine’s strategic vision and values to provide a diverse, inclusive environment that serves all people — fostering learner success, discovering and innovating, and growing and advancing partnerships.

An age-friendly world

These Americans are the most peculiar people in the world. You’ll not believe me when I tell you how they behave. In a local community in their country, a citizen may conceive of some need which is not being met. What does he do? He goes across the street and discusses it with his neighbor. Then what happens? A committee begins functioning on behalf of that need and you won’t believe this but it’s true. All of this is done by private citizens on their own initiative. The health of a democratic society may be measured by the quality of functions performed by private citizens.

Alexis de Tocqueville, 1835

The World Health Organization launched the Age-Friendly (AF) Initiative in 2006 to address the concerns of population aging. In the United States, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement teamed with the John A. Hartford Foundation to promote AF health care systems, and AARP has adopted the role of promoting and designating AF communities and counties.

Currently, there are 572 U.S. communities or counties; Maine has 72 or one in eight of all designated communities. The University of Maine Center on Aging has been instrumental in advocating for the AF designation in Maine communities and has received an AARP contract to offer training in creating the AF communities nationwide.

In Maine, as more communities get involved in age-friendly initiatives, their efforts spread by word of mouth as nearby towns begin to see the possibilities. At the Center on Aging, Patricia Oh directs the efforts in promoting and supporting AF communities, where “older adults start to mobilize.”

“They have the time, energy, life skills to make change,” Oh says. “Maybe they are recently retired and are anxious to give to their communities.”

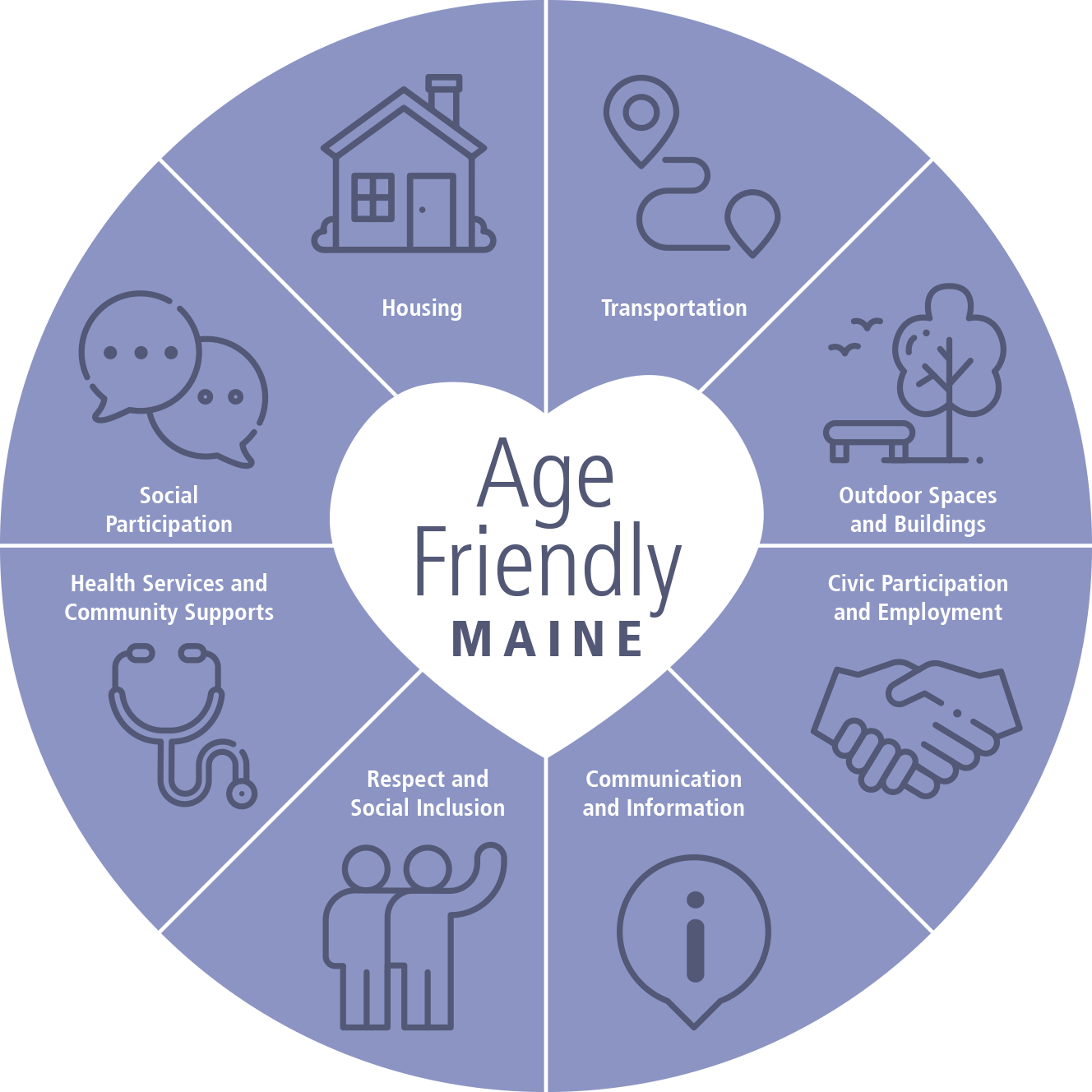

WHO’s eight domains of livability — housing, transportation, community support and health services, outdoor spaces and buildings, communication and information, civic participation and engagement, social participation, and respect and social inclusion — are designed to help older adults live healthier, more productive lives.

“When a community forms their AF group, they will read about those eight domains,” Oh says. “They are not expected to work on every area necessarily. They ask, ‘What are our strengths? What do we need in order to thrive?’ Such as a space to meet for coffee, or a volunteer transportation program, or a food delivery program. Then they build on their strengths to address those needs. They may not believe that the strengths exist in their community, but each community has what they need to thrive. It’s a matter of tapping into it.”

For example, a number of communities in Maine have started home repair programs. In its first year, Saco completed 150 service calls. Waldo County and Bowdoinham have both partnered with the Masons to provide nonlicensed services, but also worked with licensed providers to offer discounted services to older adults.

“These programs help folks to recognize how they can help their neighbors,” says Oh.

Currently, the Center on Aging is involved with two similar programs serving older adults — Lifelong Fellows and Lifelong Maine Americorps. Lifelong Fellows offers a $3,000 stipend for one community to mentor another in its support of older adults. The Lifelong Maine Americorps program brings in part-time or full-time Americorps individuals to help a community ramp up what is already being done to support older adults. Communities that engage in the age-friendly process have two years to develop an action plan, and in five years submit an after-action report, reviewing and evaluating progress.

“When I speak to town managers, I tell them it’s just good town planning,” Oh says “It’s community the way it should be.”

UMaine’s Center on Aging provides AARP-supported training to drive age-friendly communities and counties nationwide. The multifaceted contract includes providing technical support to the network. A program called Rural Lab provides targeted technical assistance to rural communities.

Oh says the Center on Aging is not affecting age-friendly outcomes, but facilitating and supporting the momentum in communities focused on the needs of elders.

“The communities themselves are the drivers of change. In Maine, this represents a grassroots effort with community residents taking charge of their own program,” says Oh.

“You should be able to be engaged in every aspect of your community and you should be able to be as healthy as possible. Age-friendly practices are helping that to happen in a remarkable way.”

Partnering to optimize initiatives focused on elders

MOST OF the University of Maine aging initiatives are collaborations with multiple entities. An outside institution may tap the university’s expertise or someone at the university seeks to bring an idea to the field. Of the 36 initiatives currently undertaken by the Center on Aging, at least 30 are partnerships working with individual Maine communities, the Maine Community Foundation, UMaine researchers, a Maine long-term care community, the Eastern Area Agency on Aging, AARP, University of New England, University of Southern Maine and UMaine Augusta, for-profits, nonprofits, and state agencies.

Last year, the Mayer-Rothschild Foundation awarded funding to the University of Maine Center on Aging and The Cedars, a nonprofit retirement community in South Portland, to identify and promote the best practices for person-centered care in nursing homes, independent and assisted-living communities, and dementia and memory care residences. The foundation’s first Designation of Excellence in Person-Centered Long-Term Care Award allows both organizations to develop a national standard for person-centered care and optimal strategies for long-term care communities to implement it. The designation of excellence they create will serve as a promotional tool for organizations that adopt best practices for this model of care. Person-centered care promotes policies that allow residents of long-term care communities to advocate for services that best meet their individual needs and preferences. While a shift toward person-centered care has taken place over the last few decades in long-term care, there is no definition or standard guidelines for person-centered care. This award seeks to move care from a model that is medically or task-driven, to care that is driven largely by resident preferences, which are often not considered.

In 2019, an initiative of the University of New England in collaboration with the Center on Aging to improve the health and well-being of Maine’s older adults through enhanced practitioner training received a five-year award of nearly $3.75 million from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under its Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program.

A statewide collaborative called AgingME will focus on improving the health and well-being of Maine’s older adults through training enhancements and practice transformation processes at the primary care level. The innovative collaboration, in partnership with Maine’s health systems leaders at MaineHealth and Northern Light Health, and federally qualified health centers, will bring together practitioners, health professions students and educators from throughout the state to improve primary care for older adults and their caregivers.

The Center on Aging is the lead evaluator for the statewide geriatrics training initiative, documenting the impact of its work by collecting input and data from students, partners, older adults and caregivers reached through program efforts.

At UMaine, AgingME efforts will entail the integration of geriatrics and specialized clinical content into simulation lab training for students in the School of Nursing Family Nurse Practitioner program and gerontology courses in the Interprofessional Graduate Certificate program for health and human service professionals who provide care to older adults in a variety of primary care practice and other settings.

In addition, the UMaine School of Social Work will develop a geriatrics student social work field practicum unit, and the School of Food and Agriculture will incorporate a geriatrics nutrition practicum for upper-level nutrition majors and graduate dietetic interns. UMaine’s clinical psychology doctoral program also will advance its training related to the health and well-being of older adults, including a comprehensive supervised experience in gero-psychological review and analysis.

“This HRSA-funded project represents an unprecedented opportunity to significantly expand the geriatrics skill set of health and human services personnel across the state, and ensures that UMaine will continue to perform a critical function in this regard, especially in the region’s most rural communities,” says Lenard Kaye, Center on Aging director and UMaine professor of social work.

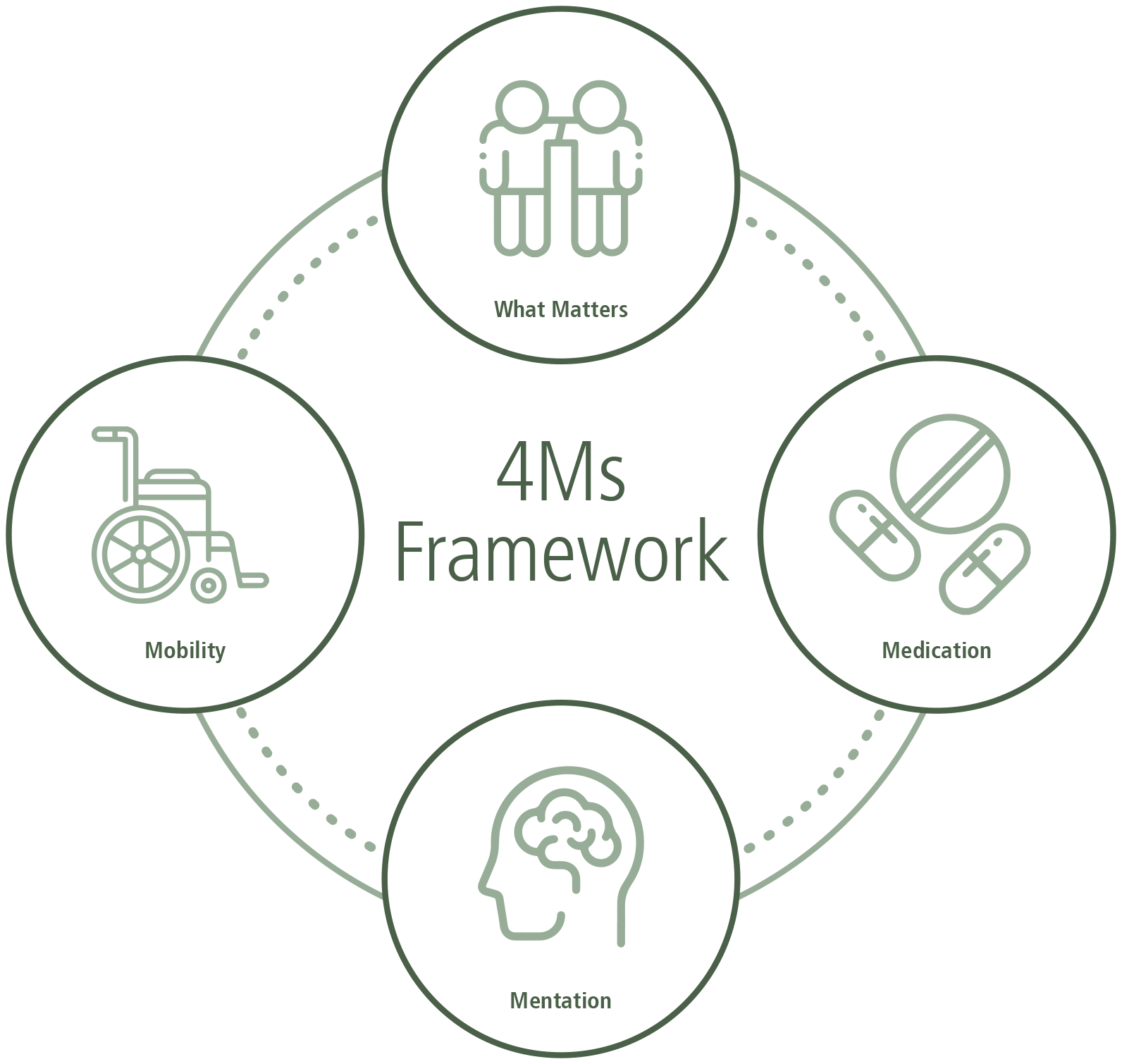

At UMaine, each of the involved departments has introduced courses or training to more fully understand the specific needs of elder patients and emphasize the interdisciplinary approach to care. That includes a focus on the 4Ms model of older adult care — mobility, medications, mentation and what matters. The 4Ms are key concerns in giving older adults the care they need. Talking with older adults about what matters most to them in their care and in their lives becomes the driving force for how a clinician considers their medical needs.

Mobility is concerned with moving daily to maintain function to be able to do what matters. Medication is concerned with prescribing what is appropriate for the older adult, and checking to make sure they are not over-prescribed or, if so, to de-prescribe, making sure not to interfere with the other areas of concern. Mentation is identified as a key concern to prevent or manage depression, delirium and dementia in older adults.

In psychology, clinical doctoral students have learned about the 4M model and gained hands-on training in cognitive and mental health assessments

Talking with older adults about what matters most to them in their care and in their lives becomes the driving force for how a clinician considers their medical needs.

from licensed clinical psychologists, professors Rebecca MacAulay and Fayeza Ahmed. In addition, a five-year curriculum for allied health field providers and UMaine and UNE students provides training workshops dedicated to improving understanding of the assessment and treatment of mental and cognitive health problems in older adults. Topics include differential diagnostic considerations for depression in late life, how to screen for memory problems, appropriate referral recommendations and resources, and factors that promote brain health (e.g., seminars on sleep health and mindfulness).

In the School of Nursing, training simulations now include RSVP volunteers to provide as realistic a hands-on learning experience for students as possible. The School of Social Work places up to five graduate students in field placements in collaboration with UMaine partners. Food science and human nutrition seniors now have a course in the nutritional care of older adults.

“A real point of this work is getting all these health-related programs working together,” says professor Mary Ellen Camire, who co-teaches the nutrition course. “When you’re working with people, you’re not just the nurse or social worker, the psychologist or the dietician, you’re all working together as a team to understand this person’s needs. We have to work together because we have so many older people now and there is a critical need for more professionals.”

Editor’s note: Rick Mundy recently started Thriving Elders, a project of idea-sharing for healthy aging. A bimonthly newsletter is available at thrivingelders.com.