Broadly defined, the humanities encompass a diverse collection of fields that explore the human experience, past and present, and inform our existence. In fostering both creative and critical thinking skills, the humanities empower us to reason and evaluate the more qualitative aspects of our world.

At the University of Maine, the Clement and Linda McGillicuddy Humanities Center champions research and outreach to promote the cultivation of cultural knowledge, intellectual curiosity, and critical and creative reflection.

In the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, world-class scholars are renowned educators and researchers in the humanities who share their expertise broadly — in the classroom, in their academic fields and in the community. And their contributions in the public sphere are multifaceted — from writing seminal books to providing leadership in humanities initiatives on local, state and national levels.

One of the many examples of this UMaine leadership in the humanities is the Department of History. Faculty members are among the top experts in their respective fields, contributing to the greater scholarship dialogue nationally and globally, and in Maine — from organizing Maine National History Day for teachers and students in grades 6–12 to editing the Maine History journal and collaborating on the state’s upcoming bicentennial observance.

That scholarship and community engagement inform the classroom experience for UMaine undergraduate and graduate students. And those leading faculty scholars collaborate with graduate students who conduct their own research.

In the case of Ph.D. students Daniel Soucier, Elisa Sance and Eileen Hagerman, that research focuses on Maine history.

Collectively, their research projects span 200 years — from the Revolutionary War in the 1770s to the small-farm revolution of the 1970s.

Soucier has studied Benedict Arnold’s ill-fated 1775 expedition to Quebec through the “howling” wilderness of Maine. Sance has explored the Madawaska French of “the Valley” and Hagerman has examined the intersect of the counterculture “back-to-the-landers” and Maine’s aging traditional farming population that ignited the locally grown and organic food movement. Their humanities research provides valuable insights into the past that has shaped the state’s cultural heritage and identity, and has the potential to inform Maine’s future.

Navigating the Eastern Country Wilderness

In early October 1775, along the Kennebec River near the small frontier village of Norridgewock, Simon Forbes noted in his diary: “This was the last English settlement on our route. Now commenced our walk into the wilderness.”

The 19-year-old was a soldier in Benedict Arnold’s expeditionary force to Quebec City to rout the British garrison there. The march required traversing a poorly charted network of rivers and portages in the vast wilderness between Massachusetts and Canada that would eventually become the state of Maine.

The soldiers had been traveling for nearly a month, sailing from Massachusetts to reach the Kennebec River, then heading farther north in a flotilla of leaky bateaux, over a series of rapids and steep falls to reach Norridgewock.

But this was just the beginning. The army of more than 1,000 then faced a journey into the unknown, untamed wilderness.

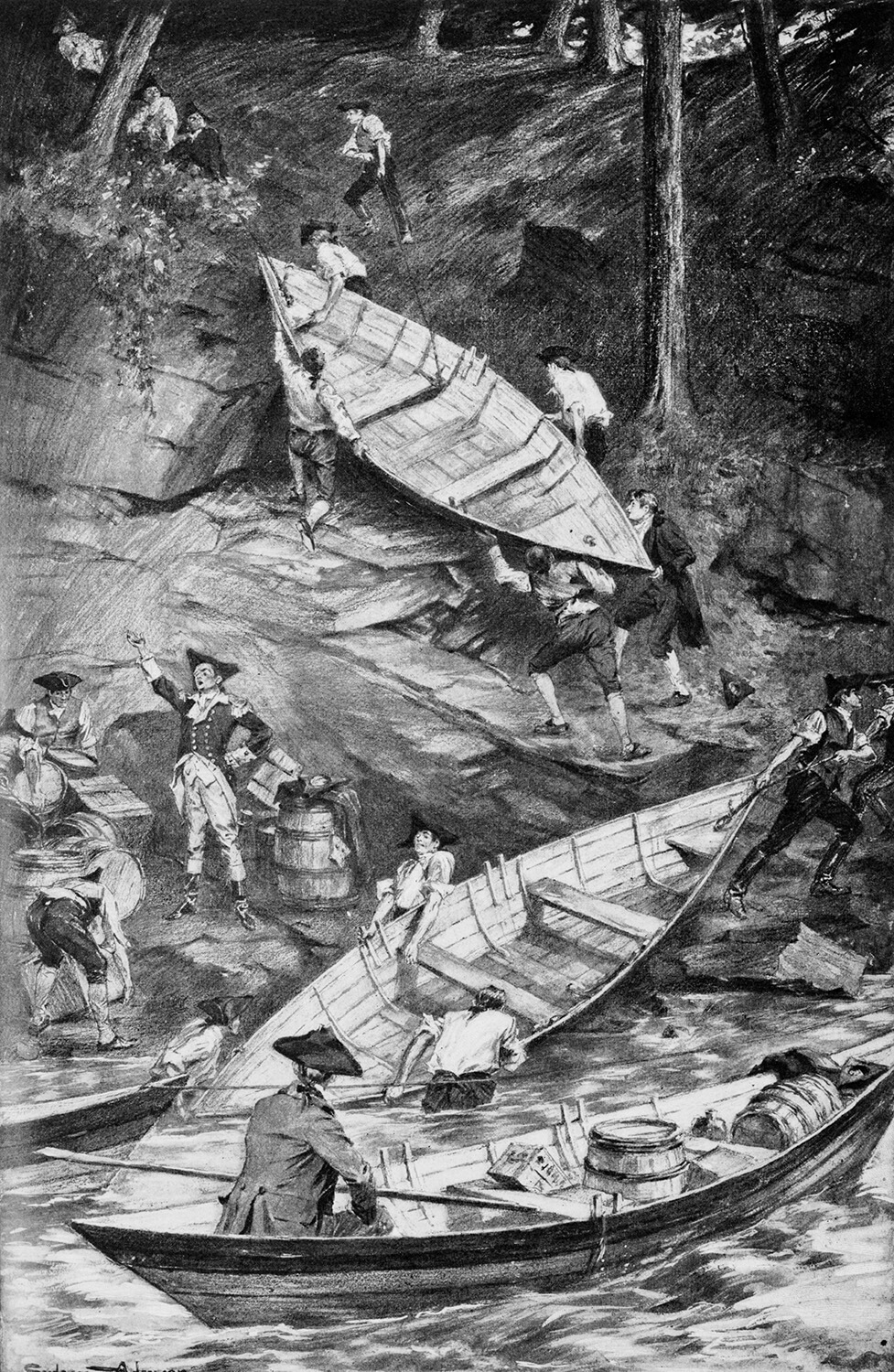

A drawing by Sydney Adamson that appeared in 1903 in The Century, an illustrated monthly magazine, depicts Arnold’s troops portaging with boats at Skowhegan Falls. Illustration courtesy of Library of Congress

According to Daniel Soucier, the region was so isolated and untraveled that muskets and other items dropped by the soldiers remained undiscovered for another 80 years.

For many early colonial Americans, the wilderness was a place of chaos and isolation, void of humans, says Soucier, who is studying how the landscapes and environments of the Northeast shaped the soldiers and conflicts of the Revolutionary War.

Through the diaries and letters of the soldiers on Arnold’s ill-fated march through the Maine woods, Soucier has learned a great deal about the environment they encountered. Their detailed firsthand accounts of the landscapes suggest a deep sense of fear and isolation, but also curiosity, wonder and reverence, despite the hardships they faced throughout their journey.

“It was fascinating to see common soldiers waxing poetically about the wilderness,” says Soucier, who likens their musings on the wilderness to those attributed to 19th-century intellectuals Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Many of the soldiers went to great lengths to catalog and understand the flora and fauna they encountered. Soucier says it was a way to assign order to the natural chaos that engulfed them.

The passages in the diaries suggest the soldiers saw the wilderness as lush and providential. The value they ascribed to each of the elements they described in the otherwise unfamiliar landscape helped the expedition navigate — even survive — the wilderness, says Soucier.

The longer the soldiers spent in the Maine woods and categorized what they were seeing, the more the land made sense, which made it a far less imposing force in their journey to Quebec.

But it wasn’t just the usefulness of their surroundings they documented and appreciated. In their writings, many found great beauty in the forest’s isolation, which perhaps distracted them from the intense hardship of the journey, Soucier says.

The march to Quebec was plagued with bad maps, bad weather and bad luck. Arnold’s map of the Kennebec–Chaudière route was incomplete and failed to account for nearly 200 miles of terrain. A severe storm, which blew through a few weeks after they left Norridgewock, flooded the area and made game scarce. Combined with the desertion of 300 of Arnold’s soldiers, who took most of the expedition’s remaining provisions, the food supply became dangerously low. Many soldiers resorted to cooking and eating anything they could stomach, including their shoes and candles.

Almost 200 others died during the march.

“Instead of being fearful of the wilderness, they were, instead, overwhelmed with complex feelings of intrigue, wonder and curiosity,” all while suffering great hardship in the Maine wilderness, says Soucier.

The members of Arnold’s expedition should be regarded equally as soldiers and amateur naturalists, he says.

“Understanding how individuals thought about the natural world during the founding movement of America can help inform our political and social discussions regarding the environment today,” says Soucier. “It shows us the intertwined histories between humans and nature.”

Arnold and his remaining soldiers barely made it out of the wilderness. They arrived at the gates of Quebec City in December, only to suffer a devastating military defeat in a New Year’s Day blizzard.

At Quebec, Forbes was captured and held as a prisoner of war. In August 1776, he escaped and made his way back to Massachusetts via the same wilderness route he and the other soldiers had used nearly a year before.

Wanted: Bilingual teachers

Many Mainers know the northern region of the state simply as the Valley. For locals, it’s “chez nous” — our place.

The Valley’s strong cultural identity is a product of its French-Acadian and French-Canadian roots, including the widely spoken dialect. Generations lived in the territory that spanned both shores of the upper St. John River.

That was until 1842, when the final border between Maine and New Brunswick, Canada was drawn. The new border split the Valley in two and the French-speaking families of the Madawaska territory found themselves on different sides of international lines.

According to Elisa Sance, the linguistic and cultural differences between the Madawaska French and the English-speaking governments of the countries resulted in many challenges in the establishment of public institutions in the area, including schools.

Sance is studying the relationships between teacher training and the education of non-English-speaking students in Maine and New Brunswick at the beginning of the 20th century. She’s particularly interested in the role of public education in the assimilation of the francophone population of the Valley on both sides of the border.

“One of the missions of a public school system is to shape the citizens of tomorrow,” Sance says. “Unfortunately, school can also be a place where one is forcefully stripped of their identity and heritage.”

In Maine and New Brunswick, English was the language of public education.

To the Madawaska French, however, English was more or less a foreign language — one that almost no one in the Valley spoke or understood.

Maine’s answer was to create the Madawaska Training School in 1878 to teach local bilingual teachers who could educate the French-speaking children.

It started as a traveling school operating in the larger communities in the Valley, then found a permanent home in Fort Kent, Maine. As the first of its kind in the state, the Madawaska Training School focused on immersion for native French speakers to become fluent in English while learning the educational subjects and skills to teach them.

In her research, Sance traced the lives and careers of the school’s graduates, who were mostly women from small communities in the Valley. Most stayed to teach in area schools, but some taught on both sides of the border.

Maine’s assimilation agenda was neither neutral nor harmless, and likely fostered a deep sense of alienation among the Madawaska French, says Sance. It may have also brought some unforeseen economic, educational and social changes to the isolated region — potential effects Sance is continuing to explore in her research.

Sance argues the assimilation effort also served as a powerful incentive for the Madawaska French to preserve their culture and traditions — including their language.

According to the recent census, two-thirds of the Madawaska population reported French as their first language. In some towns, such as nearby Frenchville or St. Agatha, that number is even higher.

And each year the region hosts the Acadian Festival to celebrate the Valley’s French heritage.

Sance, a native of France, grew up in a multilingual and multicultural family. Through her research, she hopes to highlight some of the challenges faced by minorities — like the Madawaska French — regarding their integration, identity and sense of belonging.

For three years, she taught beginner and intermediate French at UMaine and the University of Maine at Farmington, where she encountered students who expressed a desire to learn the language as a way to reconnect with their Franco-American and Acadian roots. Many of the youth had never been taught the language by their older generations out of a fear of discrimination.

“Exploring the early relationship between language, identity, citizenship and the school systems in Maine and New Brunswick can give us great insights into the history of the region. It can also inform us on how to foster better intercultural communication in our increasingly diverse societies,” Sance says.

From Youth Rebellion to Rural Renaissance

Take a drive along a rural route anywhere in Maine this summer and you will likely encounter dozens of roadside produce stands, farmers markets, and homemade signs advertising produce for sale ranging from farm-fresh eggs to eggplant. This is in addition to the restauranteurs and grocers who buy and use organic, locally grown foods from throughout the state.

There’s no doubt Maine’s locally grown organic food culture is special. Small-scale family farming has, for generations, been as much a part of the state’s cultural heritage as lobstering.

“I couldn’t help (but) notice something unique in Maine’s agriculture, something that set it apart from my home state of Kentucky and from nearly everywhere else in the country,” says Eileen Hagerman, whose research in environmental and agricultural history focuses on the development of the local food and farm movement in northern New England, including what made the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s so successful in Maine.

“Maine had begun to reverse its rural decline and was experiencing a major farming renaissance long before the ‘locavore movement’ of the 2010s arrived. I was in awe of how far ahead of the curve the state seemed to be in this regard,” she says.

According to Hagerman, much of the state’s agricultural success is attributed to the scores of back-to-the-landers who arrived in Maine during the ’70s — but not solely. Rather, it was the relationships that formed between the newcomers and their often overlooked “old-timer” farming neighbors that made success possible.

These partnerships allowed the state’s small farming communities to revive and thrive, and laid the foundation for the innovative and cooperative initiatives that followed.

The back-to-the-land movement drew scores of young, idealistic transplants to Maine’s tight-knit rural communities in hopes of starting new lives rooted in the land. Cultivated from the seeds of 1960s counterculture, and faced with growing economic and environmental concerns, many back-to-the-landers sought simplicity and self-sufficiency through an agrarian lifestyle. But few actually possessed the experience or skills to be successful farmers, Hagerman says.

Many of those who found their way to Maine were inspired by the writings of Helen and Scott Nearing, radical activists and Depression-era back-to-the-land experimenters. Their 1954 book, Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World, and its anti-establishment, do-it-yourself message resonated deeply throughout the movement.

However, by the time the Nearings’ message began drawing hundreds of back-to-the-landers to their farm in Harborside, Maine, the state’s rural communities were nearing a century of steady decline.

The increasing reliance on large, out-of-state producers and wholesalers gutted the local small-scale farming economy of the state. Farming was becoming a nonviable way of life and, as a result, many rural children were forced to leave their parents’ farms in search of better jobs elsewhere. The few small family farms that remained struggled to sell their products, and were operated by an increasingly poor and aging population, says Hagerman.

The back-to-the-landers who came to Maine found affordable, abundant, abandoned farmland, Hagerman says. Many also found something idyllically authentic in the spirit of the state’s rural people, and an opportunity to learn from them the rapidly disappearing local knowledge and traditional skills they lacked.

Hagerman says many of the back-to-the-landers would never have stayed on the land long term if it wasn’t for the initial support they received from older neighbors.

Rural Mainers have a curious reputation for being fiercely individualist and harboring a general wariness toward outsiders, she says. However they often also possess a strong sense of community.

“Maine’s rural renaissance was a hybrid movement, propelled by both the actions and interests of locals and back-to-landers.” Eileen Hagerman

According to Hagerman, due to the hardships that come with living in rural Maine — the harsh climate, short growing season, sparse population and poverty — neighborly mutual aid was as much a survival strategy as it was a virtuous way of life.

Old-timers were a wellspring of local knowledge, often built on generations of Maine farmers’ know-how, she says. More often than not, their experience in organic farming was due to frugality rather than environmental idealism. It was priceless to the inexperienced back-to-the-landers.

Concurrently, the older local farmers needed help on their own farms. Many were concerned about the survival of their way of life following decades of out-migration by younger community members, Hagerman says.

Hagerman’s research shows that older farmers cautiously placed the future of Maine farming in the hands of back-to-the-landers by adopting the newcomers as extended family and as members of their tight-knit communities.

And, thus, the stage was set for an unlikely alliance. One founded in hard work and hardship that bridged both the cultural and generational gap. The cross-cultural pollination began to turn many counterculture back-to-the-landers into stable, rural citizens, while the old-timers became accidental agrarian radicals, says Hagerman.

As Maine’s farm movement gathered steam, initiatives like the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA) were established, she says. Many of these groups were imbued with the same interdependent values of the local farmers who helped shape them. And, they slowly rebuilt Maine’s local farming economy.

“Maine’s rural renaissance was a hybrid movement, propelled by both the actions and interests of locals and back-to-landers,” says Hagerman, “and I think this story has implications for present-day discussions around the arrival of ‘new Mainers.’

“I think the back-to-the-land movement shows a precedent for Maine benefiting from its willingness to embrace newcomers and positive change. By embracing those newcomers and that change, the Maine that local people know and love can live on indefinitely.”