Regeneration debt

Extensive land development, invasive species and too many deer may make it difficult for tree migration to keep pace with climate change in the Northeast, according to a new study.

Extensive land development, invasive species and too many deer may make it difficult for tree migration to keep pace with climate change in the Northeast, according to a new study.

The research, led by Kathryn Miller, a plant ecologist with the National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Division, and Brian McGill, a University of Maine professor of ecological modeling, analyzed U.S. Forest Service data covering 18 states, from Tennessee to Maine.

The researchers found a large swath of land in the mid-Atlantic states severely lacking in forest regeneration. Even where present, species regenerating on the forest floor differed from those making up the forest canopy.

Earlier studies have raised concern about regional regeneration, but this is the first to document the sheer extent and severity of the problem, according to Miller, who recently earned a Ph.D. from the UMaine School of Biology and Ecology.

Coining the term “regeneration debt” to describe this phenomenon, the researchers found the region simultaneously faces challenges of increasing invasive plants, deer overabundance and heavy land development.

The zone of regeneration debt raises questions about the future of forests in the immediate region, but also far into the northeastern U.S., according to the researchers, whose findings were published online in the Journal of Applied Ecology.

Miller and McGill say combining this research with a 2018 study they conducted raises even more concerns. The earlier study simulated a century of seed dispersal for 15 tree species across the eastern U.S. while taking into account current land development patterns.

The researchers’ simulations revealed an area in the mid-Atlantic region with such extensive human land use that tree dispersal was effectively blocked from moving northward. The species most affected by this dispersal barrier are the same oak, hickory and pine species found to be experiencing severe regeneration debt.

Fish and fat

Some people trying to eat healthy increase their consumption of salmon, tuna or mackerel — foods rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fats (n-3 PUFA).

Some people trying to eat healthy increase their consumption of salmon, tuna or mackerel — foods rich in omega-3 polyunsaturated fats (n-3 PUFA).

People also take fish oil supplements that boost intake of vitamin D for healthy bones and muscle, and to regulate the release of serotonin, which affects appetite and stress.

And why not? The prevailing nutritional narrative is that diets that include omega-3 fatty acids and fish oil supplements are metabolically healthy, says Kristy Townsend.

But the University of Maine neurobiologist demonstrated, for the first time, that while young mice on an n-3 PUFA diet had a striking reduction in weight gain, they also sustained adipose, or fat, tissue damage and dysfunction.

That’s because the n-3 PUFAs had undergone peroxidation, a process of nonenzymatic degradation that produces toxic fatty acid byproducts.

Regardless of the source of the n-3 PUFAs, including tinned fish and fish oil supplements, as well as attempts to mitigate the process of peroxidation, Townsend found most sources contained high levels of potentially harmful peroxidized lipids.

The findings potentially have important implications for human nutrition and dietary health, says the associate professor of neurobiology.

Since the brain is second only to adipose tissue (fat, or loose connective tissue that stores energy and cushions and insulates the body) in terms of fat/lipid content, it’s important to understand how dietary fats affect brain and adipose lipid metabolites — small molecules involved in metabolism — and their cellular functions.

The types of tissue damage Townsend observed in the adipose of mice on the peroxidized n-3 diet also has been observed in people, and has been linked to underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular disease, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s disease.

The findings were published online in ScienceDirect’s Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry.

Tick testing

Photo by Griffin Dill

University of Maine Cooperative Extension is now accepting tick samples for tick-borne disease testing. Maine residents can have ticks tested for the pathogens that cause the three most common tick-borne diseases — Lyme disease, anaplasmosis and babesiosis — for $15 per sample. Species identification of tick samples continues to be free.

Testing is done at the new UMaine Extension Diagnostic and Research Laboratory in Orono.

Prior to the lab’s opening last summer, UMaine Extension was the only resource providing tick identification in the state. Now it also the only resource in Maine available to the public that offers testing for tick pathogens.

The tick identification and testing program will allow researchers to track the spread of ticks and their associated diseases in the state, while also surveying for new tick species and pathogens.

Instructions on submitting a tick specimen to the lab are online. Information on different tick species of Maine, tick management, tick-borne diseases and personal protection also is available on the tick lab’s website.

Preventing the virus that causes PML

More than half the human population is infected with a virus that resides undetected in the kidneys of healthy people. But when a carrier of the human JC polyomavirus, or JCPyV, has a weakened immune system, the virus can migrate to the brain and becomes fatal.

More than half the human population is infected with a virus that resides undetected in the kidneys of healthy people. But when a carrier of the human JC polyomavirus, or JCPyV, has a weakened immune system, the virus can migrate to the brain and becomes fatal.

The virus spreads through contaminated food or water and from person to person — as it settles in a person’s urinary tract and bone marrow, and can be shed in urine. The virus stays in these sites for a lifetime, and many people never know they have it, says Melissa Maginnis, University of Maine assistant professor of microbiology.

"This research will pave the way forward to better understand how viruses are able to sneak into cells and cause infections." Melissa Maginnis

In people with weak immune systems, the virus can travel to the brain and cause a serious infection called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which damages the outer coating of nerve cells, causing permanent disabilities and death.

Currently, there’s no cure for PML.

Maginnis, who examines the biology of JCPyV seeking to identify ways to prevent the virus from causing PML in people with suppressed immune systems, has been awarded more than $435,000 through the National Institutes of Health Research Enhancement Award program.

Maginnis, a recipient of the 2018 UMaine Graduate Mentor of the Year Award, is dedicated to providing undergraduate and graduate student training opportunities in biomedical research.

The team hopes its findings will improve the understanding of JCPyV and possible treatments for PML, and enhance the knowledge of how viruses invade cells.

Maginnis and her team published an article in the Journal of Virology that identifies specific components of the cellular pathway usurped by JCPyV to invade cells in the kidney and nervous system. The study was led by Colleen Mayberry, a Ph.D. student in the Maginnis Lab and alumna of the undergraduate biochemistry program.

Reuse value

The relationship between community resilience and reuse markets is the focus of a project led by University of Maine researchers.

Cynthia Isenhour, a professor of anthropology and climate change, and Andrew Crawley, a professor of regional economic development, were awarded more than $265,000 from the National Science Foundation to examine Maine’s reuse markets and their potential to advance social, environmental and economic public policy goals.

The study is part of “ResourcefulME,” a three-year research project designed to explore Maine’s vibrant culture of reuse — yard sales, flea markets, Uncle Henry’s, thrift stores, antique shops, community swaps, lending libraries — and the value of these practices for economic development, social resilience and natural resource conservation.

“Policies designed to encourage reuse are popping up all over the country, as cities and states have learned how effective reuse can be for climate mitigation, waste reduction and natural resource conservation,” says Isenhour, who also is a faculty associate in the Senator George J. Mitchell Center for Sustainability Solutions. “Maine already has a vibrant reuse economy, which raises all sorts of interesting questions about its cultural roots and whether there are lessons here in Maine that might be valuable for encouraging reuse in other locales.”

While recycling aims to recover reusable components and materials from waste to produce new goods, reuse refers to recirculating goods in their original form. Despite claims of economic and environmental benefits, reuse economies are significantly understudied, according to the researchers.

The researchers define reuse as the redistribution of previously owned material goods through a transfer of ownership such as a sale, swap, barter or gift, or a temporary use agreement to borrow, rent, lease, share or loan.

Isenhour and Crawley use a combination of geospatial analyses, economic modeling, surveys and ethnography to examine diverse reuse exchanges at national, regional and community levels.

Through national geospatial analyses and ethnographic grounding in rural Maine, Isenhour and Crawley aim to advance theory in studies of regionalism, place-based development, and local processes supporting economic resilience.

Name that plant

Since its inception, University of Maine Cooperative Extension has provided free plant identification for anyone with an interest in Maine flora.

Since its inception, University of Maine Cooperative Extension has provided free plant identification for anyone with an interest in Maine flora.

The newest development in this service is an online mobile-friendly, interactive Plant Identification Submission Form.

Users can enter plant information and upload photos from their computer or mobile device, and submit it to UMaine Extension ornamental horticulture specialist Matthew Wallhead.

Plant identification is particularly relevant for farmers, landscape horticulturists, nursery managers and gardeners seeking to identify varieties of crops, weeds, native plants or ornamentals.

While UMaine Extension can still receive plant samples for identification in any of its 16 county offices around the state, people also can submit specimens by emailing digital photos with descriptive information, such as whether the plant is woody or herbaceous, the plant’s size and location, when the photo was taken, etc.

After asking any follow-up questions, UMaine Extension experts can share information about the plant, which may include how to manage the invasive weed, cultivate the crop or tend to the ornamental plant.

Anthrax response

Better prediction of the emergence, spread and evolution of the environmentally transmitted pathogen that causes anthrax is the focus of a National Science Foundation award to the University at Albany, State University of New York and the University of Maine.

Better prediction of the emergence, spread and evolution of the environmentally transmitted pathogen that causes anthrax is the focus of a National Science Foundation award to the University at Albany, State University of New York and the University of Maine.

Wendy Turner, University at Albany assistant professor of biological sciences, is leading the research team on the four-year, nearly $2.5 million project. Co-principal investigator is Pauline Kamath, UMaine assistant professor of animal health. They will be joined by scientists from the University of Pretoria, University of Namibia, University of Oslo and University of Hohenheim.

Anthrax is a serious infectious disease caused by the bacteria Bacillus anthracis, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The environmentally persistent pathogen naturally occurs in soil, and can infect wild and domestic herbivore animals that inhale or ingest spores in soil, plants or water. The disease is zoonotic, meaning it can be transmitted from animals to humans following contact with infected carcasses or animal products.

The variation in anthrax outbreaks worldwide hinders successful prediction and response, according to the researchers. There is a lack of understanding of the factors driving geographic differences in the ecology of the pathogen, as well as the pattern of disease outbreaks.

The scientists will conduct research in two national parks in southern Africa where anthrax outbreaks differ in timing and severity.

The research, which uses genomics, statistics and dynamic modeling, has implications for public health, agriculture and biosecurity. It also could add to the understanding of other epidemic and emerging diseases that similarly have a variety of transmission modes, high environmental survival and wide host range. Researchers will build models to predict anthrax transmission dynamics across ecosystems.

The research will facilitate development of predictive tools to better manage public health and related policies for complex, multihost zoonotic diseases, such as anthrax.

Overlooked trends, underestimated risks

A reanalysis of worldwide annual trends in precipitation demonstrates that risk to human and environmental systems has been underestimated, according to University of Maine researchers. As a result, they found more than 38 percent of the global population and more than 44 percent of land area have been experiencing overlooked precipitation trends.

A reanalysis of worldwide annual trends in precipitation demonstrates that risk to human and environmental systems has been underestimated, according to University of Maine researchers. As a result, they found more than 38 percent of the global population and more than 44 percent of land area have been experiencing overlooked precipitation trends.

Conventional trend analysis approaches examine changes in mean annual precipitation over time, and erroneously assume that changes in high and low precipitation levels follow suit. That’s according to Anne Lausier, a UMaine doctoral candidate in civil and environmental engineering and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, and Shaleen Jain, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering.

In their paper, “Overlooked Trends in Observed Global Annual Precipitation Reveal Underestimated Risks,” published in the journal Scientific Reports, Lausier and Jain present an innovative trend typology using quantile regression and offer a comprehensive analysis of overlooked trends worldwide.

The most frequently overlooked trends include an increased risk of extreme wet conditions and increased variability found in parts of the midwestern United States, northern Canada, south-central Asia and Indonesia — home to nearly 860 million people.

Conversely, the new comprehensive analysis found 840 million people exposed to a decreased risk of wet conditions, particularly in southern Africa, South America and parts of northern Asia, indicating a decrease in the incidence of high annual totals.

An estimated 630 million people are impacted by an increased risk of dry conditions in parts of southern Europe, the western U.S., southern Canada and northern Africa. More than 40 percent of global rainfed agricultural areas are exposed to overlooked trends, including parts of southern and western Africa and the midwestern U.S.

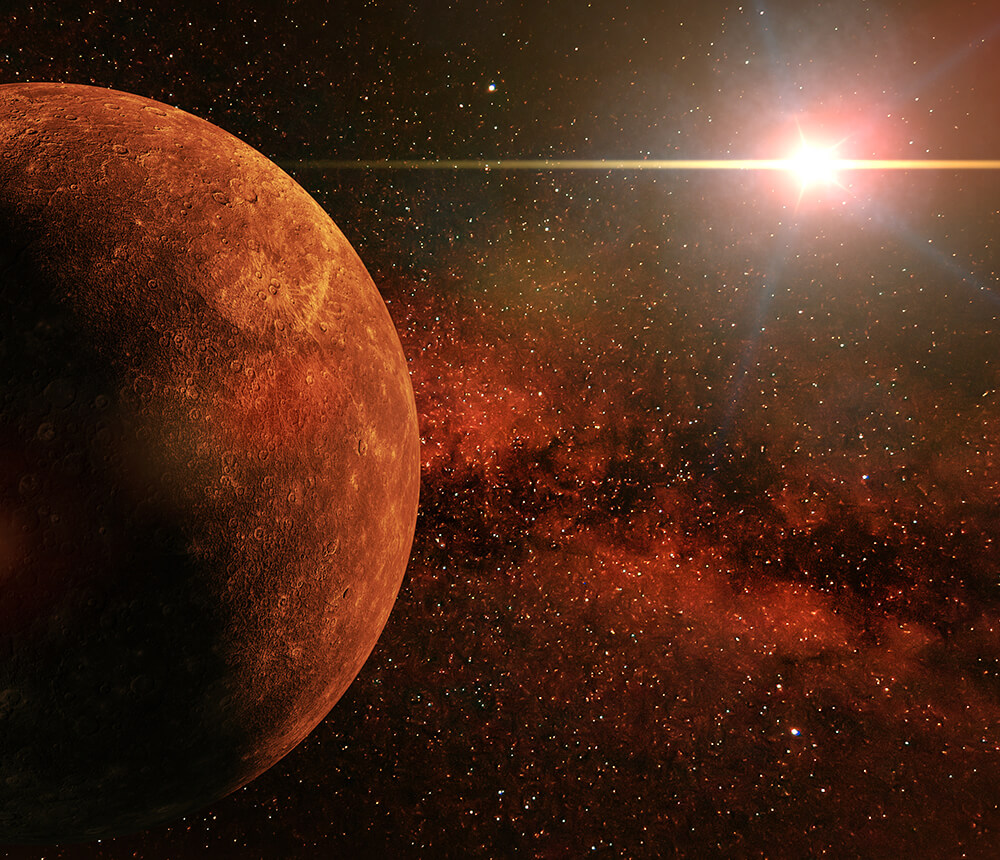

Mercury’s glaciers

The processes that led to glaciation at the cratered poles of Mercury, the planet closest to the sun, have been modeled by a University of Maine-led research team.

The processes that led to glaciation at the cratered poles of Mercury, the planet closest to the sun, have been modeled by a University of Maine-led research team.

James Fastook, a UMaine professor of computer science and Climate Change Institute researcher, and James Head and Ariel Deutsch of Brown University, studied the accumulation and flow of ice on Mercury, and how the glacial deposits on the smallest planet in the solar system compare to those on Earth and Mars.

Their findings, published in the journal Icarus, add to understanding of how Mercury’s ice accumulations — estimated to be less than 50 million years old and up to 50 meters thick in places — may have changed over time. Changes in ice sheets serve as climatic indicators.

Analysis of Mercury’s cold-based glaciers, located in the permanently shadowed craters near the poles and visible by Earth-based radar, was funded by a NASA Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute grant for Evolution and Environment of Exploration Destinations, and is part of a study of volatile deposits on the moon.

Like the moon, Mercury does not have an atmosphere that produces snow or ice that could account for glaciers at the poles. Simulations by Fastook’s team suggest that the planet’s ice was deposited — likely the result of a water-rich comet or other impact event — and has remained stable, with little or no flow velocity. That’s despite extreme temperature difference between the permanently shadowed locations of the glaciers on Mercury and the adjacent regions illuminated by the sun.

One of the team’s primary scientific tools was the University of Maine Ice Sheet Model (UMISM), developed by Fastook with National Science Foundation funding. Fastook has used UMISM to reconstruct the shape and outline of past and present ice sheets on Earth and Mars, with findings published in 2002 and 2008, respectively.

“We expect the deposits (on Mercury) are supply limited, and that they are basically stagnant unmoving deposits, reflecting the extreme efficiency of the cold-trapping mechanism” of the polar terrain, according to the researchers.

Greek history

Historically, fraternities and sororities on college campuses have mirrored broader social and cultural patterns when it comes to issues of race and racism. That includes patterns of oppression and exclusion, as well as racial uplift and cultural validation.

Historically, fraternities and sororities on college campuses have mirrored broader social and cultural patterns when it comes to issues of race and racism. That includes patterns of oppression and exclusion, as well as racial uplift and cultural validation.

University of Maine assistant professor of higher education Kathleen Gillon analyzes these themes in the latest issue of New Directions for Student Services, for which she also served as lead editor.

Gillon says the goal was “to start conversations about issues related to equity and inclusion, specifically around race, ethnicity and culture in sororities and fraternities on college campuses.”

Gillon co-wrote a pair of articles in the collection. She was lead author, with Florida State University assistant professor Cameron Beatty and Florida Atlantic University assistant professor Cristobal Salinas, on “Race and Racism in Fraternity and Sorority Life: A Historical Overview.” Gillon was second author with Salinas and California State University, Long Beach director of student life and development Trace Camacho, on “Reproduction of Oppression Through Fraternity and Sorority Recruitment and Socialization.”

In the historical overview, Gillon and her co-authors write that the earliest Greek-letter organizations in the U.S., established predominantly during the 19th century, “reflected the broader collegiate student population of the time.” Students of color were excluded from these groups, just as official and unofficial policies of segregation restricted which institutions they could attend.

In the early 20th century, students of color at some colleges and universities began forming their own fraternity and sorority groups in response to issues like housing and academic discrimination.

According to the article, Black Greek Letter Organizations “included a principle of service to the community” that differentiated them from the more socially oriented fraternities and sororities established by white students. Gillon and colleagues say this theme of racial uplift continues in many black fraternities and sororities today.

As diversity improved in higher education, multicultural fraternities and sororities started to appear on college campuses to help “create a sense of validation and cultural relevance in light of the oppression and marginalization” students of color have historically experienced.

Taking stock

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission recently accepted a new assessment of northern shrimp populations in the Gulf of Maine that relied on a computer model developed at the University of Maine.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission recently accepted a new assessment of northern shrimp populations in the Gulf of Maine that relied on a computer model developed at the University of Maine.

"With a warming Gulf of Maine, such an improvement in the model is critical for improving the quality of northern shrimp stock assessment." Yong Chen

Yong Chen, UMaine professor for fisheries population dynamics in the School of Marine Sciences, and postdoctoral associate Jie Cao created the model, which divides the northern shrimp stock into size groups. It also tracks changes in the proportion of shrimp in each size group across seasons and years to estimate fishing mortality and population size, and incorporates temperature.

The model uses data from the Northeast Fisheries Science Center Trawl Survey, the Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp Summer Survey, commercial landings and a winter sampling program conducted in partnership with fishermen.

The new UMaine northern shrimp stock assessment model considers potential impacts of temperature on the dynamics of northern shrimp stock in the Gulf of Maine — a significant improvement in the assessment of northern shrimp that prefer colder water temperature, Chen says.

Coastal climate futures

Mainers can expect significant environmental changes in the next two decades due to increased greenhouse gas emissions and patterns of variability in the climate system, say University of Maine researchers Sean Birkel and Paul Mayewski.

Their report — “Coastal Maine Climate Futures” — provides a base for coastal Maine planners to prepare for a variety of plausible short- and long-term climate challenges in their communities, where fishing, forestry, tourism and agriculture are economic cogs.

Birkel is a research assistant professor and the Maine state climatologist based at the Climate Change Institute (CCI); Mayewski is a Distinguished Maine Professor and CCI director.

Maine’s coastal climate is strongly influenced by a number of factors that determine short- and long-term changes in climate. Those key factors include El Niño/ Southern Oscillation (ENSO), volcanic eruptions and warming in the Arctic associated with increasing greenhouse gas emissions. ENSO is a particularly important feature as El Niño brings warm/dry conditions and La Niña brings cool/wet conditions to Maine.

This pattern of variability oscillates every three to five years. And the three strongest recent El Niño events (1982–83, 1997–98 and 2015–16) occurred approximately 15 years apart.

Birkel and Mayewski analyzed historical climate trends, climate-commodity connections and sources of climate variability that affect Maine to put forth five plausible climate scenarios for 2020–40. The scenarios: no additional change to the current “new normal”; moderate warming; another abrupt Arctic warming and even greater Arctic sea ice collapse; cooling from increased volcanic activity; and drying from more frequent and extreme El Niño events.

Poetry works

Educators have long recognized the power of poetry to inspire a child’s enduring passion for language. But over time, poetry instruction for beginning readers has declined in favor of other teaching methods. Now, some scholars are trying to revive it.

Educators have long recognized the power of poetry to inspire a child’s enduring passion for language. But over time, poetry instruction for beginning readers has declined in favor of other teaching methods. Now, some scholars are trying to revive it.

In an article, “Why Poetry for Reading Instruction? Because It Works!” published in the International Literacy Association journal The Reading Teacher, University of Maine professor of literacy William Dee Nichols and four colleagues discuss why early reading teachers ought to be using poetry in their classrooms.

Poetry is one of the more personal genres of writing, and has been used for centuries to provide beautiful, interesting language, according to the researchers.

Nichols and his co-authors define poetry in a broad sense, including traditional verse, nursery rhymes, playground chants and Dr. Seuss. Poetry’s rhythmic and musical qualities make it especially adaptable to different ages and learning abilities, they say. Many poems also are short enough that they can be reviewed repeatedly during lessons, making them effective tools for developing skills such as fluency and understanding.

Where have all the flowers gone?

Spring wildflowers may face challenges in a warming climate. That’s according to researchers who combined their findings with historical observations collected by philosopher and author Henry David Thoreau.

Spring wildflowers may face challenges in a warming climate. That’s according to researchers who combined their findings with historical observations collected by philosopher and author Henry David Thoreau.

Conservation biologists Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie of the University of Maine and Richard Primack of Boston University presented Thoreau’s scientific observations from the 1850s in Concord, Massachusetts to Mason Heberling, assistant curator of botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The data included tree and wildflower leaf-out dates measured for 37 separate years between 1852 and 2018. Their findings were published in the scientific journal Ecology Letters.

Primarily as a result of human activities, temperatures in Concord, Massachusetts have warmed by 3 degrees Celsius over the past century, say the researchers.

During the same time period, tree and wildflower leaf-out dates — when plants produce leaves — have shifted significantly.

“Wildflowers are now leafing out about one week earlier than 160 years ago, but the trees are leafing out two weeks earlier,” says McDonough MacKenzie, a David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellow at the Climate Change Institute. “Understory wildflowers need the sunny conditions before the trees leaf out for their energy budgets, but we didn’t know how a shadier spring would affect these plants on the ground.”

Sensor technology for geriatric health

The University of Maine is leading multi-institution efforts to provide physicians with tools to help aging people avoid falls and to detect biomarkers associated with pancreatic cancer.

The University of Maine is leading multi-institution efforts to provide physicians with tools to help aging people avoid falls and to detect biomarkers associated with pancreatic cancer.

Directed by UMaine engineering professor John Vetelino, researchers at UMaine, the University of Maine at Farmington and the University of Maine at Machias are collaborating with St. Joseph Hospital in Bangor.

“We wanted to know how the sensor technology that we are developing at UMaine could contribute to health care in Maine and beyond from the viewpoint of physicians and health care providers,” Vetelino says.

UMaine researchers and students initially met with St. Joseph doctors and caregivers, and determined that a sensor system that collected data about the gait and fall risk of aging adults could make a significant and immediate beneficial impact.

In addition, UMaine and Dartmouth College researchers have begun collaborating on a sensor system to detect biomarkers associated with pancreatic cancer.